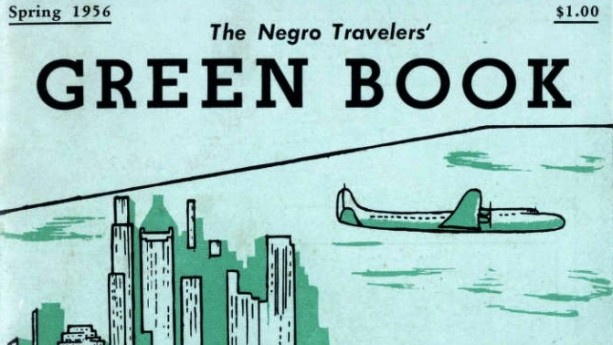

During the era of Jim Crow, many African Americans relied on this “Bible of Black Travel” to navigate safe passage and find sustenance and respite while on the road. This oral history project will identify and interview individuals who are connected to historic sites of refuge in Los Angeles – hotels, motels, restaurants, gas stations, and other businesses. Stories will be presented through public programs, an interactive website, and provide material for a book and exhibit that will document a little known chapter in California history and provide opportunities to re-examine America’s troubled history of race relations.

Tell us a little about yourself and your past documentary work.

I’m an author, photographer and cultural documentarian with a master’s degree in Visual Criticism. I produce multimedia projects in the form of books and traveling exhibits that are interdisciplinary in nature and critically investigate issues of race, culture and identity within contemporary political, social, and cultural landscapes (see www.taylormadeculture.com). My work has been featured in The New Yorker, USA Today, The Wall St. Journal, The Los Angeles Times, The San Francisco Chronicle (cover), AARP, Photographer’s Forum (cover), and on PBS and NPR. I spent over a decade interviewing people who owned restaurants, salons and barbershops for my previous projects, “Counter Culture” and “American Roots,” which also received support from California Humanities. Doing interviews with African American, Latino, and white waitresses who worked in segregated restaurants during Jim Crow, I learned how to encourage people to let down their guard and talk about race, segregation, class and identity.

How did you get interested in this topic?

I discovered the Green Book while doing research for a Moon Travel Guide on Route 66. The tourism surrounding Route 66 is a saccharine re-imagination of the postwar “happy days,” and the brand of Route 66 is so weighted down with nostalgia, parts of the fabled highway are suffocating from an idealized past that never was. The truth is, America is a messy cornucopia of customs, traditions, values and belief systems that have been shaped by capitalism, gender and race. I wanted to write a book that explores the earlier times of the route before it became a vacation destination for the 1950s nuclear family and tell the stories that haven’t been told about the minorities and women who traveled and worked on Route 66. I wanted to honor the past, not romanticize it.

Being black and traveling away from home during the Jim Crow era involved a great deal of planning, faith and a reliable travel guide called the “Negro Motorist Green Book.” Victor H. Green, an African American postal worker from Harlem published this roadside companion from 1936-1966. His “Green Book” listed restaurants, hotels, salons, barbershops, taverns, nightclubs, tailors, garages and real estate offices that opened their doors to African Americans. It was considered the “Bible of Black Travel.”

During the time the Green Book was in publication, automobile travel symbolized freedom in America and this guide was a resourceful solution to a horrific problem. The practice of racial discrimination was in full force throughout the country. Thousands of the 6 million African Americans who left the south to escape racism were stranded, beaten and lynched on the road. From the 1930s through the 1960s, America had over 10,000 “Sundown Towns,” which were all-white communities. Many of these towns posted signs at their borders warning African Americans to leave before sundown. According to the 1930 Census, 44 out of the 89 counties along Route 66 were all white. Even once travelers reached a multiracial city such as Albuquerque, their options were still limited. For example, only six percent of the more than 100 motels on Route 66 in Albuquerque accepted African Americans.

Although the South was infamous for its Jim Crow laws, ironically, it was the lack of formal segregation laws that made the rest of the United States even more dangerous for African Americans to navigate, simply because they didn’t know where they were welcome. In addition, there were fewer African Americans living in other parts of the country, especially in California, and they often didn’t see other African Americans who could offer travel advice, food, shelter and automobile services in case they needed them.

Despite the dangers, African Americans ventured out on desolate two-lane highways that connected urban and rural America. The Green Book not only offered safety and convenience, it was a powerful tool for African Americans to persevere and literally move forward in the face of racism. Being an African American woman who drives over 20,000 miles a year documenting American culture, I was struck by the simplicity and practicality of this guide. For me, the Green Book re-contextualized and reframed the all-American road trip. After learning about it, I never looked at Route 66 the same way again.

How will you go about doing the project?

The Green Book project will materialize through deep research and direct field inquiry.

Since 2014, I have been working with the National Park Service documenting Green Book properties along Route 66 and we’ve estimated that less than one-quarter of these buildings are left. The fact that we have these buildings as physical evidence of racial discrimination is an exciting and rich opportunity to re-examine America’s troubled history of segregation, black migration and the rise of the black leisure class.

My project will use quantitative and qualitative oral and field research methodologies, and gather statistical and historical data to document, evaluate, catalog and archive any information regarding Green Book sites. To access these materials I will research Green Book business owners and seek living family members to inquire about the operators’ ethnicity, gender, and political affiliation. Most Green Book business owners were African American, but my research is revealing that along with prosperous African American men and women, people of diverse backgrounds owned Green Book properties. Stories behind how and why the owners of these properties chose to integrate their businesses and the problems they faced as a result — should be recorded. I will also catalog Green Book-related materials and ephemera such as advertisements, ledgers, menus, sign-in sheets and marketing materials.

What do you hope will result from it?

Given the critical nature regarding the loss of these properties due to gentrification and neglect, and the wealth of data that will be mined from this rich, treasure trove of history, I believe the data gathered from this grant will not only be valuable to historians and archives but will also inspire and educate the masses about the struggle and triumph of literally and figuratively moving forward in America.

All of the data I’m collecting will be archived and provide source material to produce a book, touring exhibition, interactive map, website, mobile app, virtual reality platform, board game and walking tour. The California Humanities grant will enable me to partner with the California African American Museum (CAAM) to record stories and the history surrounding Los Angeles’ Green Book properties as well as to host an event on the Green Book and displaying ephemera from these historic properties. I am also working with the Los Angeles city planner to register Green Book buildings as cultural and historic sites to be included in the Los Angeles Historic Resources Inventory and published on the Historic Places LA website.

I have not decided on a publisher yet, but Cornell University and Beacon Press are interested in the project and I am also exploring the possibility of developing a larger exhibit in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) and the Schomburg Center for Black Research.

Why do the humanities matter?

The humanities matter because they add context and meaning to our everyday lives and help us discover a new way to think about culture and identity. Without the humanities there would be fewer ideas about how to engage community, stereotypes would go unchallenged and society would be doomed to repeat the same mistakes.

Images Right to Left: Dunbar Lobby, St, Clair, Owners of the St. Clair

Helpful Links: National Park Service Video, Candacy’s Website.

.jpg)