Project Description:

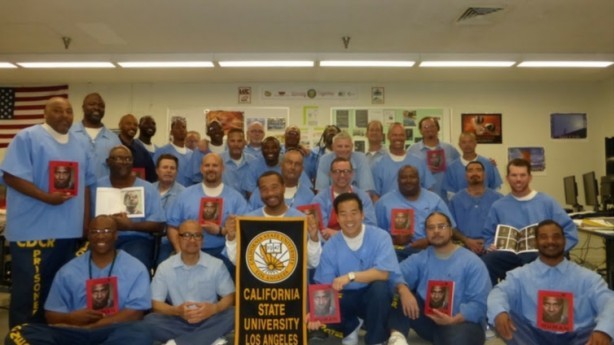

WordsUncaged aims to enable a group of men sentenced to life or life without the possibility of parole (L.W.O.P), who are participants in two educational programs at Lancaster State Prison, to reflect on and share their experience with the broader public through writing and visual storytelling. Through multiple means, the project will add the voices of these Californians to the broadernarrative about life in our state, and contribute to the public conversation about incarceration. To date, the project has produced a print and digital book, an installation and public event in Los Angeles, and a website. Additional exhibitions will be held at the CSULA library and Sherman E. Burroughs High School in Ridgecrest. All materials will be housed in a digital archive at the CSULA library. The project is directed by Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy of the CSULA English Department under University sponsorship.

Please tell us a little bit about the project – where did the idea come from?

The idea first began through my participation in the Paws for Life dog program at Los Angeles County Prison LAC). We created a writing program for participants to reflect upon the transformative experiences of the dog program that grew into various other writing and literature classes and, eventually, culminated in the creation of Calstate LA’s first in-person BA degree in a California prison. Throughout this process, I soon realized that the prisoners had remarkably powerful stories to tell; they simply needed a platform to let their voices be heard. Hence WordsUncaged was born as a creative, interactive, exhibit for incarcerated artists, writers, students and poets to dialogue, and critically engage with the public. Together, we created a website, a literary and art journal, as well as an art exhibit that ran for the month of April at Ave 50 Studio in Los Angeles. The goal of this project is to bring voices, uncaged from the prison walls, to the public in order to rethink who prisoners are as human beings, and to imagine new ways of understanding our current system of mass incarceration in California, as well as alternatives to it.

The idea first began through my participation in the Paws for Life dog program at Los Angeles County Prison LAC). We created a writing program for participants to reflect upon the transformative experiences of the dog program that grew into various other writing and literature classes and, eventually, culminated in the creation of Calstate LA’s first in-person BA degree in a California prison. Throughout this process, I soon realized that the prisoners had remarkably powerful stories to tell; they simply needed a platform to let their voices be heard. Hence WordsUncaged was born as a creative, interactive, exhibit for incarcerated artists, writers, students and poets to dialogue, and critically engage with the public. Together, we created a website, a literary and art journal, as well as an art exhibit that ran for the month of April at Ave 50 Studio in Los Angeles. The goal of this project is to bring voices, uncaged from the prison walls, to the public in order to rethink who prisoners are as human beings, and to imagine new ways of understanding our current system of mass incarceration in California, as well as alternatives to it.

How did you go about implementing the project? How did it unfold?

Did you experience any challenges? What was surprising?

Because the goal of the project was to collapse the distance between prisoners and the outside world— to stress what we have in common as human beings—our approach was to make the project as collaborative and dialogical as possible. Students at Calstate LA read, edited and gave feedback to the writers and artists at LAC and photographer F. Scott Schafer came to the prison to take photographic portraits of the men that looked stunning as oversized prints at the exhibit. We also had actors Amad Jackson and David Shipko perform dramatic readings of the men’s works and musician Tim Stafford write an album with five prisoners via a letter exchange program. While this collaborative process was extraordinarily impactful for all those involved—both inside and outside prison—it also represented a number of logistical challenges. Maximum security prisons, by their very nature, do not lend themselves to the free exchange of information and ideas so meeting deadlines and keeping track of edits and exchanges was a constant challenge. Despite this, the project exceeded all our hopes and expectations; it was an impressively collective experience.

What do you hope will result from the project – what sorts of impacts are you hoping to see or have seen already?

We have already seen a number of powerful impacts from the project thus far. It was very moving to see how many family members of the incarcerated attended the exhibit and events, travelling from as far as Stockton and Las Vegas. For them, witnessing their loved ones represented with dignity and beauty— as human beings—was tremendously important because, as one family member put it, it gave the opportunity to be proud of their loved ones and produced a sense of hope that one day California’s system of mass incarceration might change.

The impact of the project, however, went far beyond those with direct links to the prison. One of the most remarkable outcomes was the impact that the journal had upon youth that are often described as “high-risk.” A teacher in Santa Ana told us about a student who was already involved in gang life at 14 and who was on the precipice of dropping out of school. This student had difficulty at school and had no interest in reading, yet upon seeing a copy of the journal, which the teacher had by chance borrowed from a friend, he became engrossed in reading it until finally the teacher had to tell him that the school day had ended. The student asked if he could get a copy of the journal and his teacher drove all the way to the exhibit to find out how to get one. We have since donated a number of copies of the journal to the school. It is remarkable see how these men’s words can help heal the communities that they had once harmed.

Another important outcome was getting a copy of the journal presented to our governor, Jerry Brown. One of the contributors to the journal, Ken Hartman, had just had his life without parole sentence commuted by the governor after of 30 years in prison and so it was serendipitous for us to share Ken’s story with him. Reading Ken’s story not only served to reaffirm the decision that the governor had made but, just as importantly, enabled him to see that there were many more like Ken at LAC who deserved mercy in the future.

What are your plans for the future of this project?

Our goals for the future are to further develop its achievements thus far. We have a second edition of the journal planned for next spring that will focus on the theme of healing and restorative justice. As part of this next edition we are partnering with a number of community organizations to empower the men at LAC to have a positive impact upon their communities, as well as to dialogue with victims of violent crime as part of a collective healing process. Our hope is to expand the narrative of justice from being understood exclusively in terms of punishment and vengeance, toward imagining the restorative possibilities that an expanded understanding of justice might hold.

What does this project demonstrate about the value and importance of the humanities?

WordsUncaged showed that the power of the humanities comes from the critical and imaginative frameworks that they give us to understand ourselves and others as human beings. Prisoners, are amongst the most insightful in teaching us the value of the humanities because they have had their humanity and dignity stripped from them and, consequently, are acutely aware of questioning what it means to be human. Without the humanities, we would not have been able to think through the connections between the aesthetic and social dimensions of our project. For example, beauty was an important element of our project because it signaled that prisoners are of value and are worthy of being seen as human beings, rather than reductive stereotypes. This idea shaped numerous details of our project, down the type of paper we used to print the journal. Many of the men, who had been down for 20 or 30 years, had never touched paper of such high quality and texture; the very act of touching the paper, upon which their words were printed, was itself an empowering experience. At the same time, it signaled to a public audience a sense of dignity and value toward a group of people who are widely dehumanized in our culture and society. In this respect, the choice of paper was also a significant social and political act because it implicitly signaled certain foundational concepts of human rights, such as dignity and respect for all human beings. These sorts of choices were numerous and varied throughout the project and without training in the humanities, we would have lacked the critical frameworks through which to dialogue and think through the nuances of how to proceed with our project. In ways such as this, we hoped to show the value of the humanities by encouraging audiences (who are widely excluded from these discourses) to experience the force of the humanities through the beauty and dignity of the prisoners’ voices, rather than alienate such audiences with overly specialized theoretical language.

WordsUncaged showed that the power of the humanities comes from the critical and imaginative frameworks that they give us to understand ourselves and others as human beings. Prisoners, are amongst the most insightful in teaching us the value of the humanities because they have had their humanity and dignity stripped from them and, consequently, are acutely aware of questioning what it means to be human. Without the humanities, we would not have been able to think through the connections between the aesthetic and social dimensions of our project. For example, beauty was an important element of our project because it signaled that prisoners are of value and are worthy of being seen as human beings, rather than reductive stereotypes. This idea shaped numerous details of our project, down the type of paper we used to print the journal. Many of the men, who had been down for 20 or 30 years, had never touched paper of such high quality and texture; the very act of touching the paper, upon which their words were printed, was itself an empowering experience. At the same time, it signaled to a public audience a sense of dignity and value toward a group of people who are widely dehumanized in our culture and society. In this respect, the choice of paper was also a significant social and political act because it implicitly signaled certain foundational concepts of human rights, such as dignity and respect for all human beings. These sorts of choices were numerous and varied throughout the project and without training in the humanities, we would have lacked the critical frameworks through which to dialogue and think through the nuances of how to proceed with our project. In ways such as this, we hoped to show the value of the humanities by encouraging audiences (who are widely excluded from these discourses) to experience the force of the humanities through the beauty and dignity of the prisoners’ voices, rather than alienate such audiences with overly specialized theoretical language.

Learn more about the project HERE.