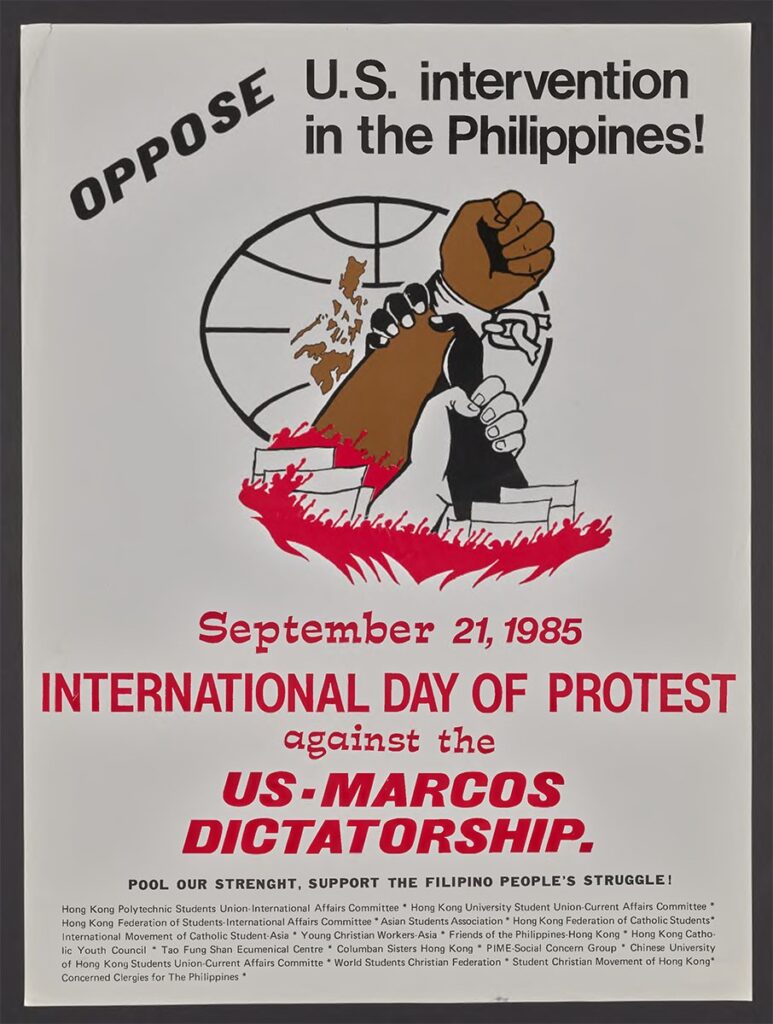

Above: Poster from The International Day of Protest on September 21, 1985 against the “US-Marcos Dictatorship,” held on the anniversary of the declaration of martial law in the Philippines. The protest was organized and sponsored by many student organizations, many of which were based in Hong Kong. Events such as these reveal the international reach of anti-Marcos resistance.

In recognition of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, we interviewed Lucy M. Burns and Karen Umemoto, directors of the Humanities for All Project (HFAP)-supported Never Forget: Filipinx Americans and the Philippines Anti-Martial Law Movement, based at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). This project is documenting the little-known transnational history of Anti-Martial Law Movement (AMLM) in California and its impact on the Filipinx community through the development of a digital curated exhibit of political posters along with interpretive content (including oral histories, essays, and recordings) and public programs (in-person and virtual) developed for and with community partners.

Ahead of their exhibition launch on June 6 (see below), the project team has made progress in poster digitization, research, and website development, with over 155 posters digitized and rehoused and research conducted on the creation of poster metadata. They are also at work identifying and drafting exhibit content, conducting supplemental oral history interviews, and developing their exhibition web platform.

We encourage you to attend the official launch of Never Forget, happening on June 6, 2023 from 12:30 – 2 pm at UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center. Stay tuned for the online exhibition and more public events this spring by following UCLA’s Asian American Studies Department on Instagram and Facebook.

Who was Ferdinand Marcos, and what did his rise to power mean for the people of the Philippines and Filipino Americans?

Lucy: Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. was the 10th president of the Philippines, ruling from 1965-1986. Ferdinand and his wife Imelda were charismatic leaders who promised to modernize and elevate the Philippines in the global political, cultural, and economic arena. On September 21, 1972, Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law through Proclamation 1081, centralizing government power, suspending civil rights, shutting down the media, silencing and criminalizing dissenters, and enforcing the rule of law through the military. Marcos’s justifications for Martial Law were numerous, including disrupting the long-standing Philippine oligarchy and defeating the communist threat. While Marcos’s rise signaled an era of dictatorial power and violence, it also meant the rise of new resistance movements against authoritarianism and U.S. imperialism that have continued into the present-day.

What was the Anti-Martial Law Movement (AMLM), and how did it involve Californians?

Lucy: Throughout Ferdinand Marcos’s 21-year reign over the Philippines, resistance movements took shape, continued, and developed alongside and against the regime’s power. An oppositional, transnational, coalitional movement formed to expose the atrocities of Marcos’s regime (including U.S. support of his administration). Due to intense political suppression and violence, his regime spurred a diasporic resistance movement and overseas international campaigns organized by people who fled the Philippines. This movement intimately connected Filipinx communities all over the world in their protest, including those in California. Many Filipinx migrants settled in California during this period, joining an older community of Filipinx farmworkers and setting the stage to become one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the state. The histories of Californian Filipinx American communities cannot be told without exploring the Marcos years and the transnational Anti-Martial Law Movement (AMLM) that sought to remove him from power.

What was the significance of choosing the visual medium of political posters as the centerpiece of this project?

Lucy: The AMLM produced stunning art, but the graphic visualizations and messaging in the form of posters represent important historical events, strategies, and sentiments within the movement.

Since part of the upcoming exhibit is to educate young people about the AMLM, using visual materials in today’s multimedia-rich environment is particularly meaningful.

What do you hope visitors to your exhibit and participants in your public programs will learn?

Karen: History repeats itself if we don’t learn from it. Authoritarianism is not an artifact of the past. Dictatorial regimes remain. Moreover, the rise in right-wing extremism and concentration of global wealth today is further eroding democratic representation in many industrialized nations, whether through the role of money in politics or gerrymandering and voter suppression. By learning from the AMLM, younger generations today can understand the dangers of such concentrations of wealth and power and the abuses that concentration allows. Visitors and participants will also see that they can change the course of history to defend democratic freedoms and human rights.

Has working on this project changed the way you think about the relationship between academic and public humanities, and what advice to do you have for others who would like to bridge the two to create public humanities programming?

Karen: The field of Asian American Studies was born of a desire among 1960s student and community movements to make education relevant and accessible to our communities. The Never Forget exhibition accomplishes three goals in this regard. First, it releases archives held at an academic institution to the wider public, with historical overview and poster information written by academic experts in the field. Second, it uplifts the voices of those in the community —activists in the AMLM— for everyone to learn from. And third, public programming invites exchange between those at the university and the wider public to deepen understanding of the artifacts and connect the past to the present.

How can people stay engaged with your project?

Karen: We hope that students, creatives, teachers, activists, and educational organizations can utilize the digital exhibition and accompanying histories as well as the oral histories in their work, to educate more people about this history and its relevance today. The posters are part of a larger collection, and we hope that we can raise the funds needed to process the larger collection to make it available to the public.

About the authors:

Lucy Mae San Pablo Burns is Associate Professor of Asian American Studies at UCLA, and Karen Umemoto is Professor of Asian American Studies at UCLA. Both are co-principal investigators of Never Forget.