At the end of November, California Humanities partnered with AMC Theatres to host a screening of the new film Green Book, starring Mahershala Ali and Viggo Mortensen. The film, based on the story of Italian American bouncer and driver Tony “Lip” Vallelonga who is hired by Dr. Don Shirley, a Black virtuoso pianist, to escort him on a concert tour of the south during the Jim Crow era. After the film screening, historian and professor Kenya Davis-Hayes, Ph.D. joined California Humanities Board Member Wenda Fong for a Q&A about the historic Green Book and its significance for Black travelers through the better part of the 20th Century. Below, Dr. Davis-Hayes shares the real story of the Green Book and the incredible places it listed, some of which still stand today. In 2019 we published a list of notable locations throughout the state that the Green Book listed, some of which are still open today.

See Part II of this blog post, by California Humanities staff.

This holiday season many Americans are preparing to venture across the nation to visit family, friends or simply take a vacation. During the Thanksgiving season alone, AAA reported that over 48 million Americans took to the roads.[1] Since the 1920s, “road tripping” has been an integral part of the American experience due to the advent of the automobile. While previous generations viewed long distance travel as a test of their ruggedness and endurance, by the 20th century, Americans were enticed by automobile ads to travel the “open road” and seek leisure, educational experiences or simply feel free. Alongside this new fervor came a whole host of support industries that further supported American travel across new and expansive highways including gas stations, roadside restaurants and travel motels or “guest cottages.” But as many Americans came to see road trips as an exciting aspect of modern American life, long distance drives did not necessarily hold the same allure for many ethnic minorities or even single women.

African Americans, in particular, struggled to enjoy the open road due to the realities of Jim Crow statutes which could be found across the nation and not simply in the South. Quite often it is assumed that segregation existed only within Southern states but black travelers quickly learned that segregation, “sun down towns,” or overt individual racism could, at best, hamper their travel experiences or at worst, lead to violent attacks or death. Still, African Americans chanced interstate highway travel particularly during the post-WWII era leading Lester Granger, the head of the National Urban League in 1947 to write, “So far as travel is concerned, Negroes are America’s last pioneers.”[2] This was further articulated in a 1950 Negro Digest article which stated, that black travelers

“gained admittance to all but the cheapest of restaurants and the most flea-bitten of hotels…travel for Negroes inside the United States can become an experience so fraught with humiliation and unpleasantness that most colored people simply never think of a vacation in the same terms as the rest of America.”

Still, Ebony Magazine reported in 1958, 20% of black households planned to purchase a new car in that year alone.[3] For the black community after WWII, automobile ownership served as a mark of middle-class status and growing numbers of families with disposable income stood willing to brave the open road in hopes of vacationing or simply visiting family scattered across the nation.

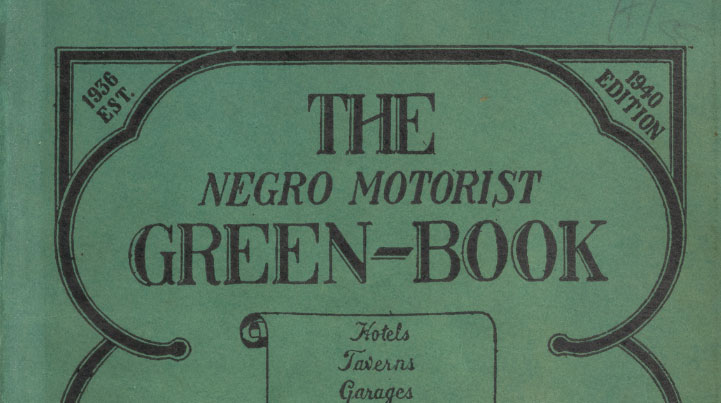

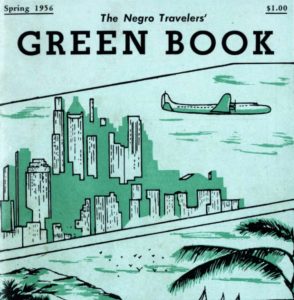

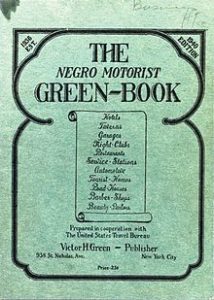

This growing desire became a clearer possibility with the publication of Victor Hugo Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book. Green was a postal worker in New Jersey and stories vary about the nascence of his Green Book. Some versions assert that Green took cues from guides published for Jewish Americans who also faced discrimination while traveling. Others claim that Green had close ties to black musicians with horror stories of traveling the nation to fulfill set engagements. Either way, in 1936 Green compiled a list of restaurants, hotels, service stations, taverns, nightclubs, drug stores and salons catering to an African American clientele around the New York Metropolitan area with the assistance of other black postal workers using their intimate knowledge of various communities. For the areas that did not have available hotels, Green compiled a list of “tourist homes” or private homes willing to rent rooms to black travelers. Over the next three decades, the Green Book expanded to every state in the Union and included international travel destinations in Mexico, Canada and the Caribbean.

Selling for between 25 cents and one dollar, Green Books promised black travelers “Travel Without Embarrassment” and throughout the years, Green asserted,

“There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published… That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please…”[4]

No state in the Union was exempt from the Green Book. While Southern states had a plethora of Jim Crow laws that governed race-based interactions, Western racial codes could also be spotty. According to Green Book scholar Candacy Taylor, “the 1930 census listed 44 of the 89 counties along Route 66 as ‘sundown towns – all-white communities that posted signs stating that blacks had to leave by sundown.”[5] These unknown codes which did not always have overt markers made travel guides even more imperative to unsuspecting black travelers. From the early 20th century through the 1950s, black travelers marveled at the limited options for accommodations. Though California seemed liberal in comparison to states across the Deep South, there were no quality hotels in Los Angeles that took black patrons before the 1920s; similar dynamics could be found in San Diego and San Francisco. It took the enterprising skills of black business people to found historic hotels like Los Angeles’ Dunbar Hotel on Central Avenue which finally ushered in a glory day of black leisure in Los Angeles while similar establishments like the Douglas Hotel in San Diego also became go-to sites for black travelers. It is important to mention that the creation of exclusive black hotels also fed into glamour and fame of black performers and other elites. The Dunbar Hotel regularly hosted stars like Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Similarly, the Douglas Hotel in San Diego hosted greats like Billie Holliday and billed itself as the “Harlem of the West.”[6]

As predicted by Victor Hugo Green, the Green Book, as well as, many of the all-black establishments it advertised declined and then disappeared with the passage of civil rights legislation banning segregation. As early as the 1950s the state of California banned the segregation of public spaces and in 1948, the Supreme Court ruled race-based housing covenants to be unconstitutional and unenforceable.[7] In 1964, the Civil Rights Act dealt a final blow to public segregation and African Americans flocked to hotels, restaurants and other spaces historically off-limits to them and their families. Finally, black motorists had the opportunity to travel the nation with the assurance of road assistance and rest. The end of The Negro Motorist Green Book era was bittersweet. While black Americans finally had full access to American travel and leisure, the institutions which had welcomed them for 30 years declined. Many were ultimately either destroyed or refashioned, leaving only historical markers in their place and archives in public libraries and historical societies across the nation remembering their names.

See Part II of this blog post, by California Humanities staff.

Footnotes

[1] “More than 54 Million Americans to Travel this Thanksgiving, The Most Since 2005,” AAA News Room, (Nov. 8, 2018). https://newsroom.aaa.com/2018/11/thanksgiving-travel-forecast-2018/

[2] Allyson Hobbs, “Summer Road-Tripping While Black,” New York Times (Aug. 31, 2018). https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/31/opinion/sunday/summer-road-tripping-while-black.html?imp_id=663260137&action=click&module=Opinion&pgtype=Homepage

[3] Thomas Sugrue, “Driving While Black: The Car and Modern Race Relations in Modern America,” Automobile in Life and Society. http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Race/R_Casestudy/R_Casestudy3.htm

[4] DeNeen Brown, “’Life or Death for Black Travelers’: How Fear Led to ‘The Negro Motorist Green-Book,’” The Washington Post (June 1, 2017). https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/06/01/life-or-death-for-black-travelers-how-fear-led-to-the-negro-motorist-green-book/?utm_term=.17f82aacfd36

[5] Candacy Taylor, “Route 66’s Legacy of Racial Segregation,” The Guardian (Feb. 27, 2015). https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2015/feb/27/green-book-south-west-usa-route-66-civil-rights

[6] Further reading on the topic of jazz and Hollywood greats and the Dunbar Hotel can be found at the following link. https://www.kcet.org/history-society/when-central-avenue-swung-the-dunbar-hotel-and-the-golden-age-of-las-little-harlem A similar topic is covered in the Journal of San Diego History regarding the Douglas Hotel. https://www.sandiegohistory.org/journal/v54-1/pdf/douglashotel.pdf

[7] 1948: Shelley v. Kramer, Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston Timeline. http://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1948-Shelley-v-Kramer.html