Pictures from the Field

October 19, 2017–March 29, 2018

In the summer of 1975, a young photography student spent months in the Salinas Valley, watching farmworkers make history. Mimi Plumb shot dozens of rolls of 35 mm film, packed all the negatives up in boxes, and went on to a distinguished career as an artist and educator. But she never forgot that summer. When she retired from teaching, Plumb went back to the boxes of negatives with the hundreds of images she had captured four decades earlier.

[tie_slideshow]

[tie_slide]

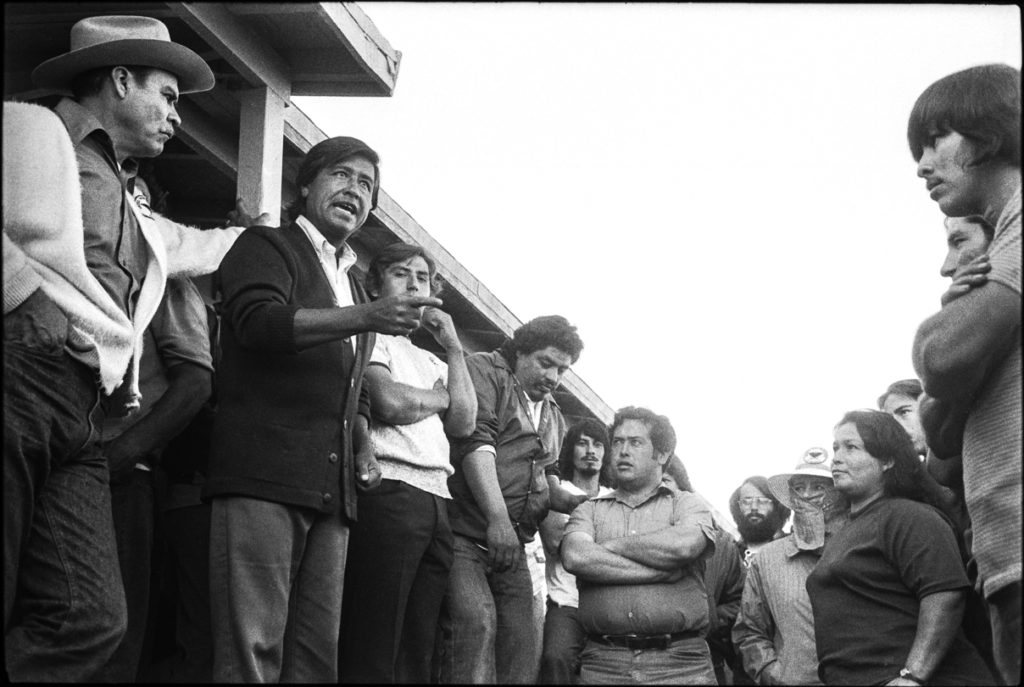

Cesar Chavez speaking at a labor camp in Salinas, August 2, 1975

On July 1, 1975, Cesar Chavez set out to walk 1,000 miles across California, from the U.S. – Mexico border north along roads that bordered tomato, strawberry, and lettuce fields, citrus orchards and vineyards – the places where farmworkers would soon make history. In two months, they would be able to petition for state-sponsored elections and cast secret ballots for the union of their choice. Chavez planned the route of his Caminata (the march) to pass through dozens of towns, so he could talk to workers in small groups along the way to explain how the law worked and how it might change their lives. In the evenings, the United Farm Workers (UFW) held larger rallies. The first section of the march started in San Ysidro and culminated a month later in Salinas after a ten-day walk through the Salinas Valley, home to the largest number of farmworkers.

Cesar Chavez is pictured here speaking at a labor camp outside Salinas during the Caminata. Salvador Bustamante (far left) was one of the guards who watched over Chavez, who had received various threats over previous years.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

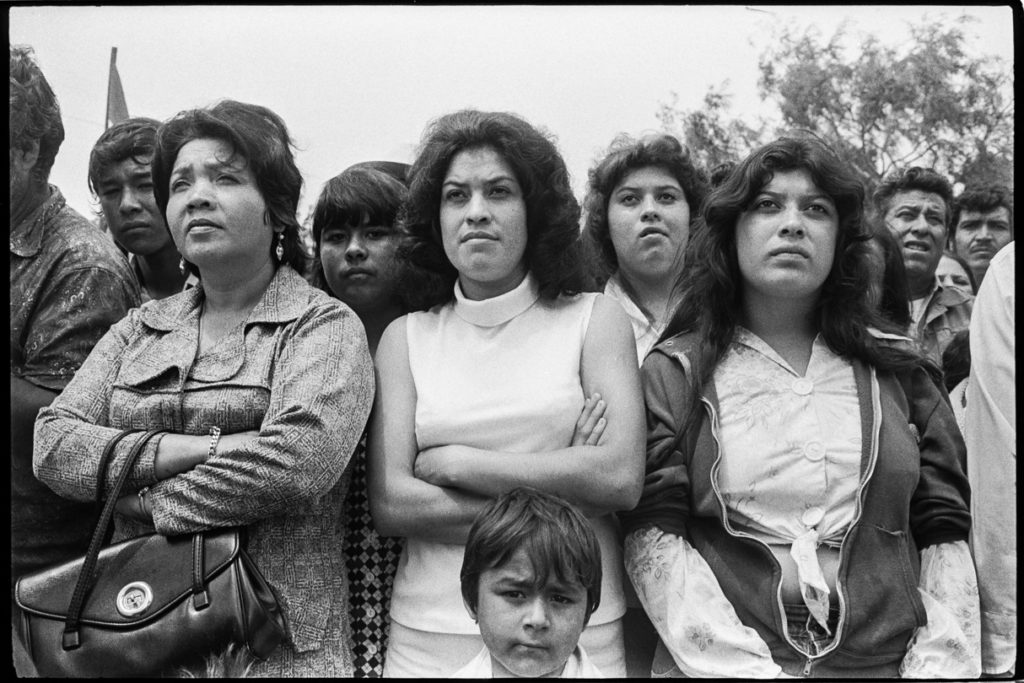

Women listening to Cesar Chavez speak at a rally in Oxnard

Women were influential to the farmworker movement grassroots mobilization. Oral history account from Robert Garcia serves as a microcosm of the role women played in the struggle for farmworker rights. In 1970, Robert Garcia was a 27-year-old foreman in the Salinas Valley, making good money. He had worked his way out of the fields and was driving a bus for a large vegetable grower. When the UFW came to the Salinas Valley, the growers refused to negotiate with the union, and thousands of workers walked out of the fields in protest. Robert’s mother, Guadalupe, was one of the first to join the strike.

Robert recalled his mother saying:

‘Mijo, you should join us.’ And I was saying, ‘I don’t need to join anything.’ She said, ‘Don’t you feel there should be justice for us? Don’t you feel that we need to be treated like human beings?’ At that time, I was a foreman. I used to treat farmworkers like dirt, too. I think that the best organizers for some of us in those days were the people that worked for the company. Because there was no respect. They treated farmworkers like machines.

I had never heard about Cesar before. I wasn’t into all that stuff. I was a foreman for Mann Packing. And my mom and my dad decided to join the farmworkers union, and they wanted me to join the strike. I told my parents, ‘No, you guys do whatever you want to do, I’m going to stay, cause they are going to pay me good money. I’ll continue being a foreman. I don’t care about the strike or anything else. I’ll support you guys, don’t worry about the rent or food or anything, I’ll take care of you guys. You just follow whatever you want to do. That’s on you.’

So I was driving the bus, taking farmworkers who were breaking the strike. One day I saw my dad, picketing at Mann Packing. My dad was holding a picket sign. I saw a sheriff knock him down, take away his huelga flag. He just threw him down. I said, ‘You don’t have to do that. All he’s doing is holding a flag – and you attack him.’ I thought, ‘There’s something wrong with this picture.’ I felt pretty bad; They didn’t need to treat farmworkers like that. They weren’t doing any harm to anybody. All they wanted was better wages, better treatment. So I decided to walk off the job. I told my crew, ‘Let’s go, let’s get out of here. I’m not going to take this.’

My mom was really the inspiration. She was really hard core. She had always been a farmworker, and she knew how they treated them, and I guess she saw something coming that would be better for them. Better pay. They had to go to the bathrooms anyplace, especially the women. The union talked about toilets, and a medical plan, and unemployment for farmworkers. ‘Justice for farmworkers,’ that’s what she said. I remember that. She said, ‘Justice for farmworkers. Finally, there’s someone that has enough courage to stand up and fight for us Mexican farmworkers.’

Everywhere there was a vigil, my mom was there. There was no place the Virgen de Guadalupe walked that she didn’t walk. That was her patron saint.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

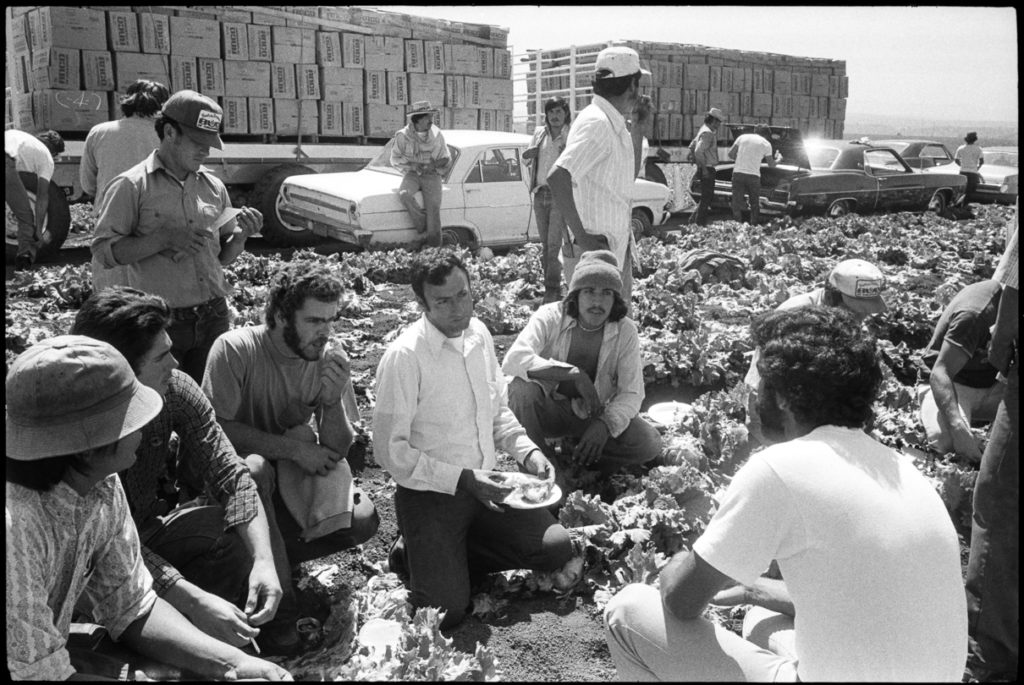

Chuy Salano speaking with workers in the lettuce fields in Salinas Valley

Forty farmworkers were hired to work fulltime in the Salinas Valley for the UFW in the summer of 1975 to help organize their coworkers and win elections. They were paid token amounts, at most $100 a week, far less than they would have earned in the fields. But for many it was an entry into new, exciting worlds. Chuy Solano (pictured bottom right corner) worked for the UFW to inform workers of their rights in the union during work break periods. He went into the fields before work, during the first break at 9:30 a.m., and for a half hour at lunch time. Just his presence in the fields impressed workers with the power of the new law.

“The people who work under United Farm Workers contracts, we own ourselves. We make our own contracts. We discuss them, negotiate them, sign them. And we enforce them. I know my rights and my benefits. Now it’s time for me to start helping people, to open their eyes and see what’s going on.” – Chuy Salano

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Marcher in Salinas Valley

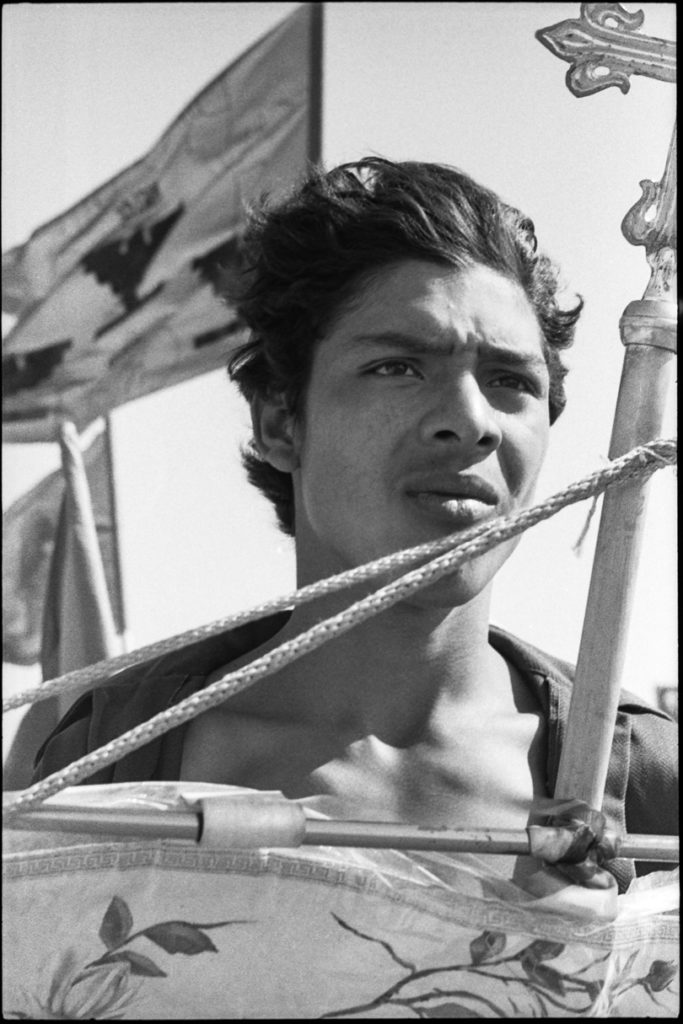

Workers took turns carrying homemade versions of the traditional United Farm Workers flag.The UFW flag featured a black eagle on a red background — the symbol adopted in September 1962 by the first farmworker organization that Chavez and Delores Huerta convened the National Farm Workers Association, the predecessor of the United Farm Workers Union.

“The idea of the march is to try to make all the farmworkers who suffer, all your families, understand that what these days are about is something very important. And we are trying to make this clear in a way that they will then understand that this is so important that we are ready, with you, to make a sacrifice, to walk 1,000 miles, from San Ysidro to Salinas, and from Sacramento to Delano, Bakersfield, La Paz. So in this very palpable way, in a very real way, to honor all the farmworkers, that what these days are about is very important, so important. We are prepared, together with you, to sacrifice so that everyone understands that this is necessary, that we cannot wait, and that all farmworkers who want a union to improve their economic and social life — now is the time.” – Cesar Chavez, August 3, 1975

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

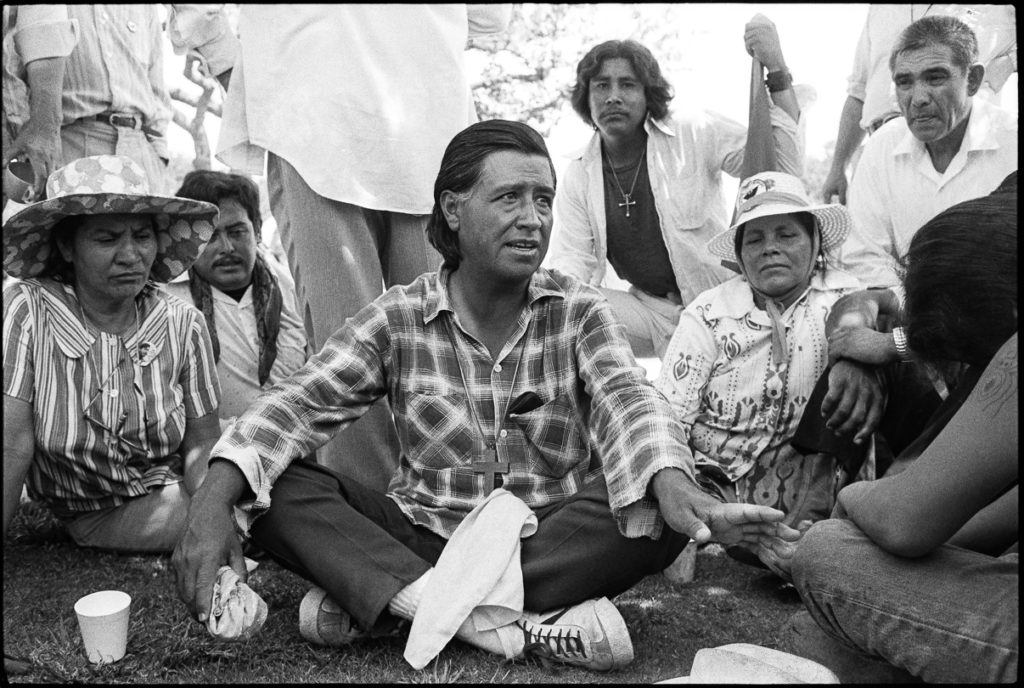

Cesar Chavez, Camp Roberts, July 26, 1975

On July 26, 1975, the temperature reached 100 degrees and the marchers stopped to rest at Camp Roberts, an old Army base at the southern end of the Salinas Valley. Chavez talked about the importance of the new state law giving farmworkers the right to protected union activity and state-sponsored elections.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Marchers Heading to King City from San Lucas in Salinas Valley, July 29, 1975

Always at the front of the march was a banner with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, patron saint and an important cultural symbol for many Mexicans and Mexican-Americans.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

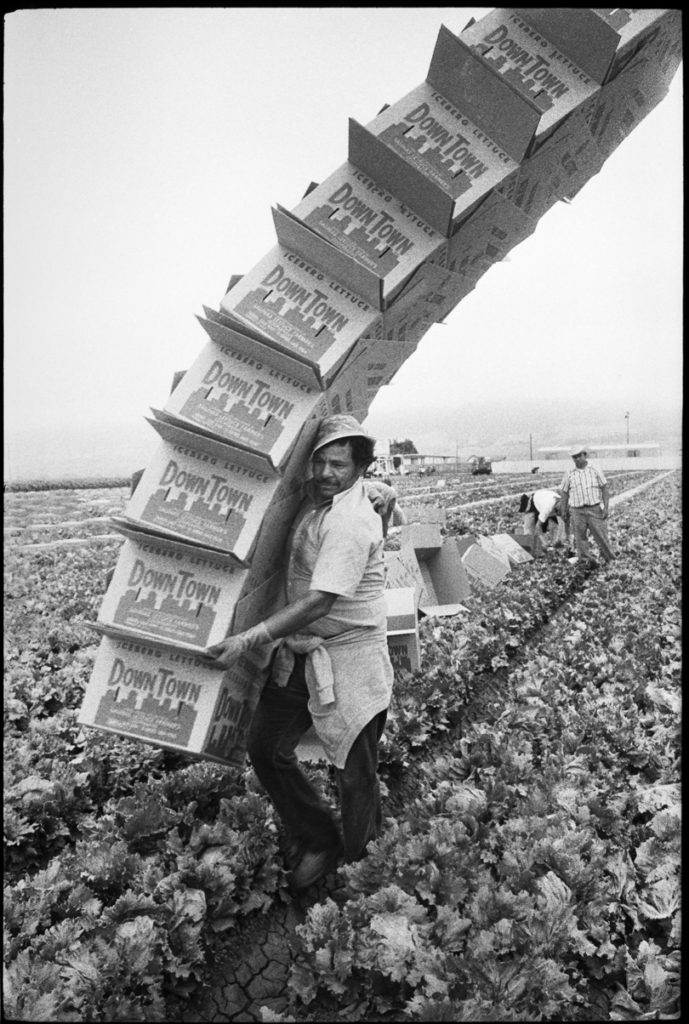

Downtown, Salinas Valley

A worker balancing a tower of boxes twice his height as he walks carefully down the rows of lettuce headed “Downtown” to cities across California and the country.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Maria Cervantes preparing lunch in Salinas Valley, August 2, 1975

Maria Cervantes is pictured here preparing lunch for Cesar Chavez. Maria opened her Salinas home to union organizers who needed a place to eat or sleep, including Chavez who often stayed there. Chavez walked between ten and twenty miles and then was driven back and forth to rest stops and overnight stays at missions or supporters’ homes.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Mariachi in Greenfield, July 30, 1975

On July 30, 1975, after 29 days and 465 miles, Chavez and the marchers entered the small city of Greenfield and were greeted by mariachis.

Chavez addressed another large audience that night:

“The sixth of June this year, there was a miracle in California. On that day, Governor Brown signed this law. It’s a unique law. The farmworkers’ law. The law gives us hope for a brighter future for ourselves, and many benefits. Brothers and sisters, the time is now! You are creating a campaign, a movement, a consciousness.”

But they must work to make the law meaningful, he warned:

“The law, then, can be used as a tool. Because the law is not enshrined on a piece of paper. For it to have life, for it to be worth something, for it to mean something, you have to use it. You have to deal with it. If not, nothing will work.”

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

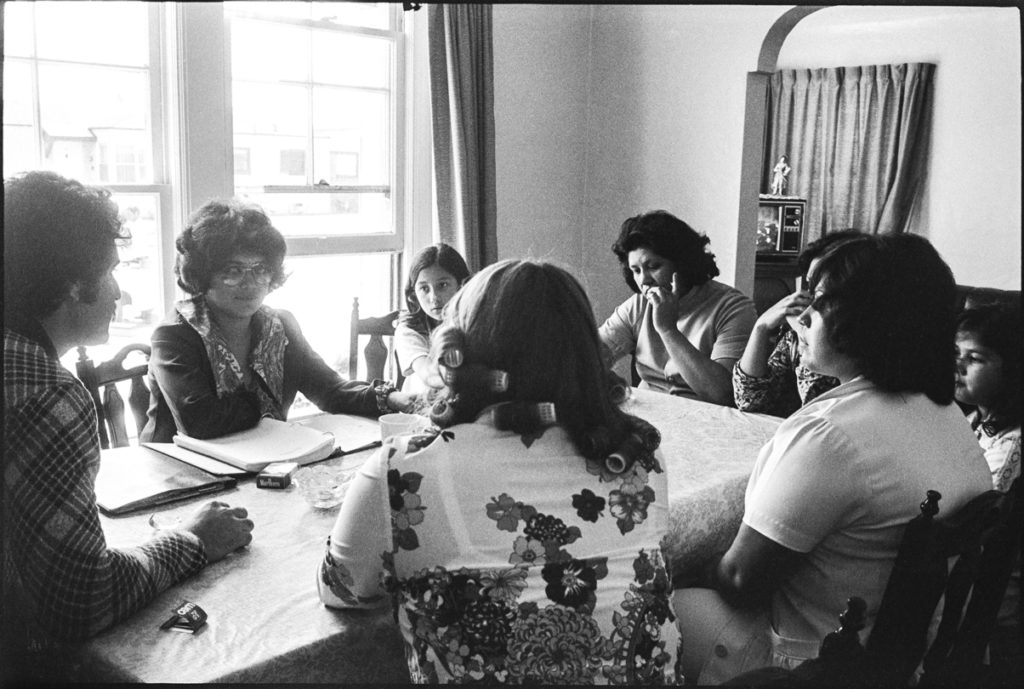

Mario Bustamante in Salinas Valley

Mario Bustamante had left his home in Mexico City as a teenager to find his father, Salvador, in California. Mario followed his father into working in the lettuce fields, and then a few years later, into the United Farm Workers.

Mario Bustamante (far left) a lettuce-cutter turned union organizer, holding a meeting in his Salinas home. The UFW educated and convened workers in small groups in their homes as well as in the workplace. His 8-year-old daughter, Isaura (center), listened, too; she grew up with a sense of the importance of fighting for social justice. She now works in a migrant education program in Nebraska.

“I learned that people are much more comfortable talking about things in their homes, rather than at work.” – Mario Bustamante

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

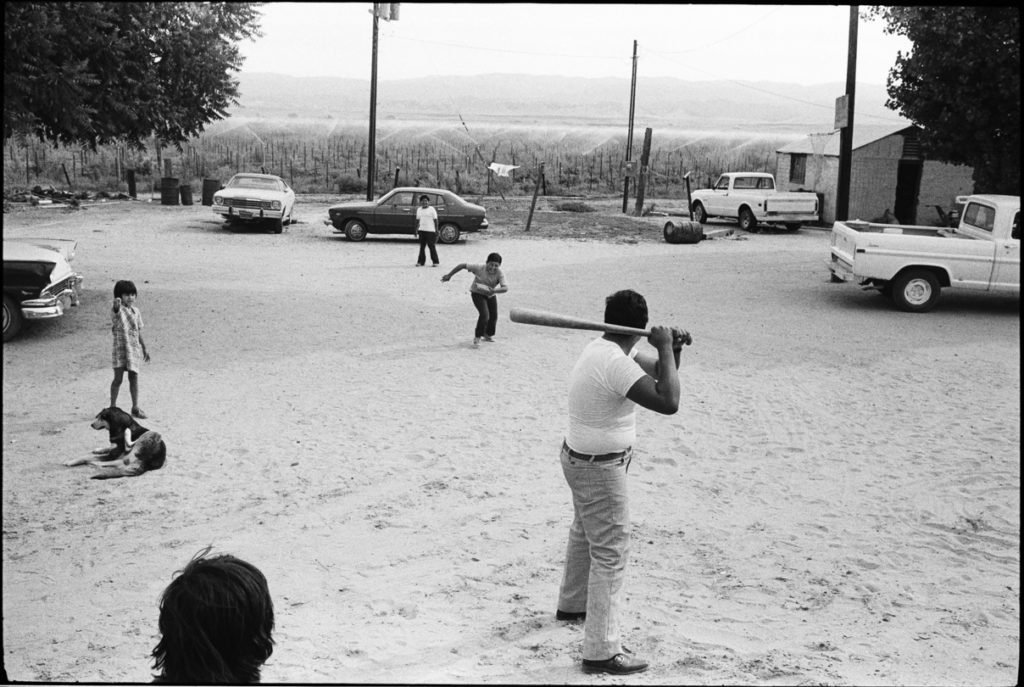

Children play baseball in a labor camp in Salinas Valley

This image is a perfect example of how family life in farmworker communities continued amidst the struggle for social change and justice.

I have six girls. I never got them involved in big things for the union. Honestly, my wife didn’t like it. She never was opposed to me doing what I did, and I thank her for that support. She saw it was something good for the whole family. But she didn’t want to get involved. I took my daughters, when they were little, I took them to knock doors, walk with me in the streets and get the vote out sometimes. Because the union wasn’t only organizing in the fields, we were organizing for change in the political system. I tried to engage them in that kind of process to see those things I was doing, to motivate them to be involved. But the union stuff, not so much.

But they were looking at me all the time. I had the flyers all the time in my car, all the things I was carrying. They knew what I was doing, they saw me everywhere. I didn’t know how much, until they grew up. My older daughter went to San Jose State, and then she decided to become a social worker. At one point we were talking and she was talking about people’s needs, and I said, why are you doing this? She said, ‘Papi, you don’t realize it, but we’ve watched you, and you had an impact on us. We were influenced by what you had done with your life. So without you saying anything, or telling us what to do, and even though we didn’t say anything to you, we have seen all that you did. And that motivated me to do something, on a different level, but similar in that it is also about helping people. – Sabino Lopez, Organizer

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Men sewing a flag in Salinas Valley

Workers from each of the dozens of ranches in the Salinas Valley designed and sewed flags with the name of their company to demonstrate the depth of support for the UFW. They assembled the flags in the Salinas UFW office to prepare for the arrival of the Caminata in the valley.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Teatro Campesino performer in Salinas Valley

The Teatro Campesino was born on the picket lines of the grape strike in Delano in 1965, when Luis Valdez returned to his hometown and began teaching farmworkers to improvise skits thateducated and entertained.

A decade later, the theater troupe had achieved international acclaim and settled in what would become its long-term home, San Juan Bautista, just north of the Salinas Valley. Though independent of the UFW, the Teatro continued to supported la Causa and performed frequently at union rallies.

One thing had not changed, The Teatro’s blend of pointed humor in improvised skits that lampooned growers and authority figures. They used humor to reduce the powerful to the very human, to help overcome fears and instill in farmworkers a sense of their own power.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

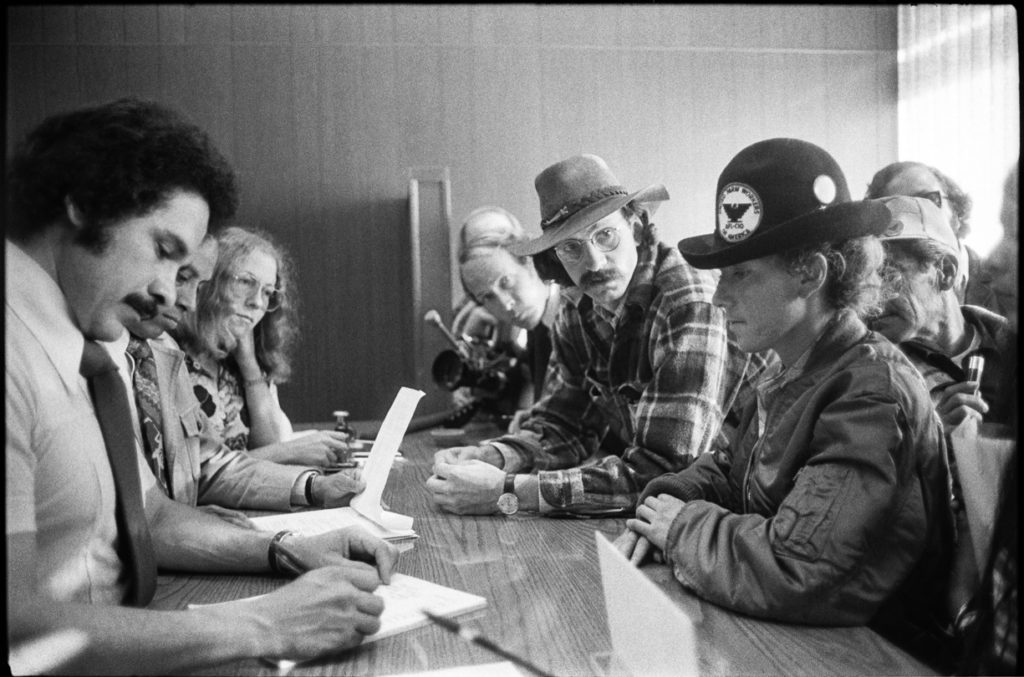

Agricultural Relations Labor Board office, Salinas, September 2, 1975

Union lawyer Sandy Nathan (center, in hat and glasses) and UFW organizer Rosa Saucedo (in hat) on the morning the Agricultural Relations Labor Board office opened filing a petition for an election at the D’Arrigo Company.

At 8:00 a.m. when the office opened, the UFW’s rival, the Teamsters union, tried to sneak in to file the first petitions. But the workers who had waited all night in the cold swarmed in protest, determined to achieve this symbolic first. After the UFW prevailed, organizer Marshall Ganz and attorney Sandy Nathan addressed the waiting crowd:

“We have just filed 19 petitions for Oxnard, Santa Maria, and Salinas, representing 5,500 to 6,000 workers,” reported Marshall.

“We’ve got one week to keep working on these ranches – and then all the other ranches in the valley, and we’re going to need everyone’s help to get the elections done in the next five, six, seven days,” said Sandy

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

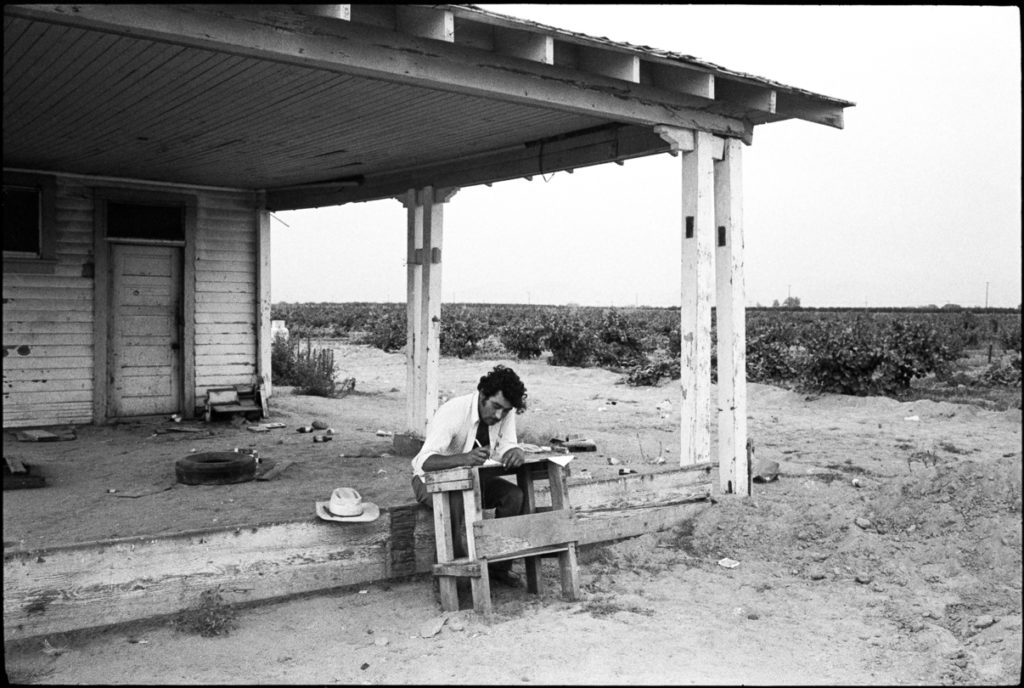

A man writing in labor camp in Salinas Valley

There are so many people who have yet to be identified in Mimi Plumb’s collection from Salinas Valley. Some worked for the UFW as organizers or in the fields; others attended union marches and rallies. In some cases, we have a name, without any more information. For most, not even that. Since they are an important part of history, author and journalist Miriam Pawel – the creator of the Democracy in the Fields website (demointhefields.com) – is asking for any information you might have about the gentleman pictured or others featured in the on website.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Artichoke farmworkers in Salinas

Three months after the Agricultural Labor Relations Act was signed by Governor Jerry Brown on June 6, 1975, the first elections to unionize farmworkers were held on September 5, 1975 at the Molera Farms Company, a small artichoke ranch in Salinas, California. Vidal Oseguera, a farmworker at Molera Farms, had organized his 14 coworkers and had each of them sign a card so they could petition for an election. By chance, their vote was scheduled first. The brand new state agency set up the polls in a shed on the farm.

Vidal Oseguera was close to tears as he explained how he organized his fellow workers:

“There were few of us, and we knew that people in the union were working very hard at the larger companies. The workers at all the small companies should be able to organize themselves, because that way we will have greater strength, and that way we will win.”

During the first month alone, more than 30,000 farmworkers voted in 1975 elections around California. Over the next few months, hundreds more elections took place – more in the Salinas Valley than any other region. More than 9,000 votes were cast for the UFW, 5,300 votes were castfor the Teamsters, and 2,000 votes for No Union.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

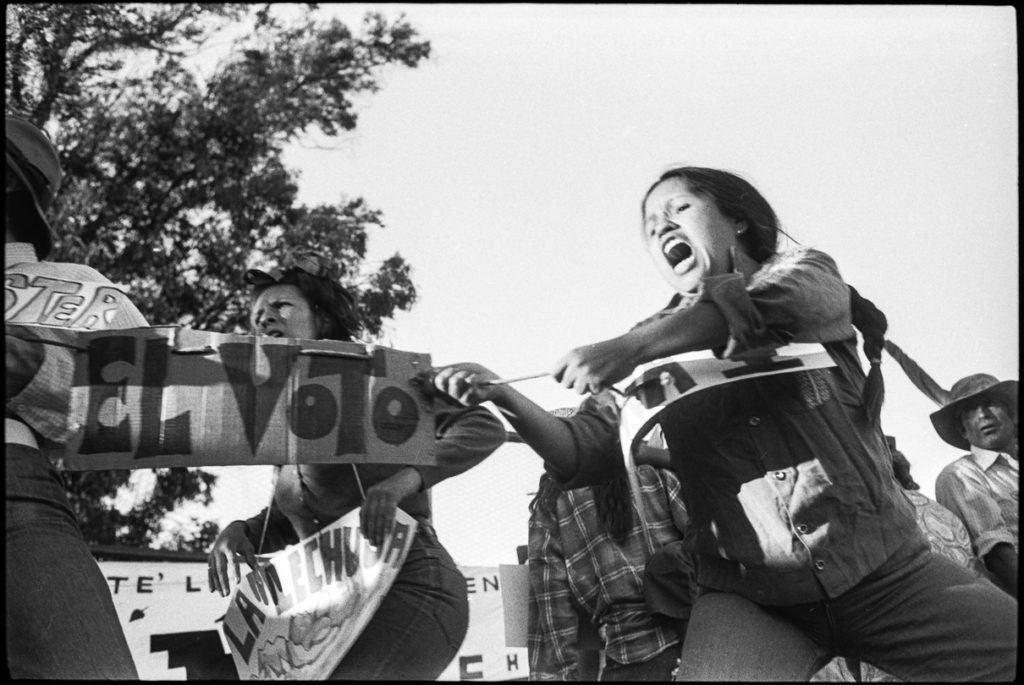

March on Gallo in East Oakland

Several hundred members of the United Farm Workers of America began a 110‐mile march in Union Square, San Francisco to focus attention on their nationwide boycott of Gallo wines. The march was a part of the boycott against Gallo winery in Modesto, the nation’s largest winery. The boycott started in the summer of 1973 when Gallo decided not to renew its contract with the farmworkers and signed instead with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, with whom the farmworkers union has been competing to organize the state’s field hands for a decade. The march featured rallies in six cities — Oakland, Hayward, Pleasanton, Livermore, Tracy, and Manteca — between San Francisco and Modesto, with farmworkers staying in the homes and churches of local supporters.

[/tie_slide]

[tie_slide]

Mario Hernandez in Salinas Valley

Mario Hernandez taking a turn leading the march, carrying the banner with the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who first appeared to an indigenous peasant on a hilltop outside Mexico City in 1531.

[/tie_slide]

[/tie_slideshow]

All images © 1975-2016 Mimi Plumb

Exhibit Opening

Exhibit Closing

[divider style=”solid” top=”20″ bottom=”20″]