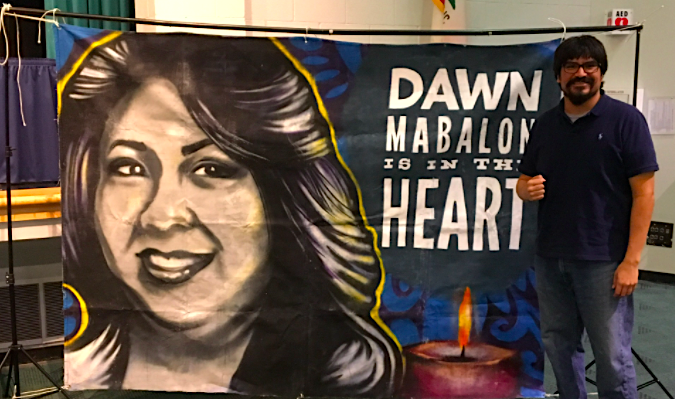

For the second offering in our new series of questions for California Humanities board members, we interviewed Dr. Oliver Rosales, Professor of History at Bakersfield College, and our new Board Chair. He is active in the humanities in the Central Valley and beyond, and a 2021 recipient of a National Endowment for the Humanities grant for the project, “California Dreamin’: Migration, Work, and Settlement in the ‘Other’ California.” He resides in Bakersfield, California, with his wife Brenda and two children. We are glad to share some details about his NEH project, the Levan Center for the Humanities at BC, and family life.

1. Representing Bakersfield College, you were a recipient of a 2021 Landmarks of American History and Culture grant from the NEH, along with Dr. Adam Sawyer at CSU-Bakersfield, for your project “California Dreamin’: Migration, Work, and Settlement in the ‘Other’ California.” What are the project goals, and how is it coming together?

I’m very excited to implement this project in Summer 2023. This grant builds off a previous NEH Humanities Initiatives project I finished in 2021. While the latter focused on faculty at my institution, the landmarks program will allow Adam and I to build a learning opportunity for K-12 teachers across the nation using landmark sites in the San Joaquin Valley: Allensworth, Delano, Arvin, and Keene, CA. The four sites highlight the multiracial histories of the valley’s agricultural labor force. Adam and CSUB were perfect partners as he directs the liberal studies program for teachers, and the university has residency capacity. Adam and I have also collaborated together for over a decade, so we have a lot of love for the valley and are ecstatic that the NEH invested in us to do this project for teachers.

2. Bakersfield College is known for its robust humanities programming; the Norman Levan Center for the Humanities is notable among California’s community colleges. How does the Center add to BC’s student life and engage the local community? And how did the late Dr. Jack Hernandez, the first director of the Center, envision its role at the start and develop it over the years?

Everyone at Bakersfield College misses Jack Hernandez. For over a decade, Jack built a robust public humanities culture at Bakersfield College with generous funding provided by Norman Levan, the late doctor, and philanthropist. At the time, the Levan gift was the largest individual donation to any community college nationwide. The Levan Center has a variety of public programs, including book clubs, heritage series lectures, faculty research funding, student scholarships, adult learning, as well as an annual keynote lecture featuring a world-renowned speaker. A philosophy instructor at Bakersfield College since the mid-1960s, Jack believed the humanities provided a public good and helped us better understand the human condition and improve civic life. Norman Levan also cared deeply about Hispanic and Native American culture, so the Levan Center has developed annual programming to highlight Hispanic and Native American research opportunities for students. It’s a wonderful center and community partner for humanities in Bakersfield.

3. As the father of two young children, how do you navigate family life – particularly during a pandemic – while also being so active in the academic and public humanities? And are your kids future humanities scholars?

Like so many others, the pandemic has been both a blessing and a curse. For myself, probably more of a blessing in the sense that working from home has allowed me to spend so much quality time with my little ones at such a formative stage. My kids love to garden and are pretty good at growing all sorts of vegetables. They also love historical photos and going through my library, as I did with my father’s books. My wife and I have also learned a few new family meals in our culinary repertoire. I’ve also enjoyed the transition to virtual humanities programming. While there was a learning curve, I think virtual humanities programming is here to stay. It’s convenient, interesting, and allows us to do public humanities in an equitable fashion for people facing transportation barriers, which has always been a challenge for underserved humanities communities in Central California.