California Humanities is proud to be a winner of the Schwartz Prize for outstanding work in the public humanities. This recognition awarded at the 2020 National Humanities Conference, held virtually this year, is for our Library Innovation Lab, an ongoing capacity-building and professional development program that helps California’s public libraries develop innovative programs that engage their immigrant communities. Over the last four years, the program has engaged more than 33,000 Californians and over 40 partner libraries who provide welcoming experiences for immigrants and foster more inclusive communities. Congratulations to fellow Schwartz Prize recipients Humanities Texas, Vermont Humanities, and Humanities Washington.

We are happy to share reflections from staff and board members who attended the 2020 National Humanities Conference, produced by the Federation of State Humanities Councils and the National Humanities Alliance:

Cherie Hill, Communications Manager

2020 marks my first year attending the National Humanities Conference. A newbie to the humanities councils, attending such a significant networking opportunity from my computer posed challenges, but I felt instantly engaged in attending sessions on the first Friday. The Council Communications Officers meeting began with fun and movement as moderators Melanie Moore Richeson, and Angela Speakman asked us to participate in a zoom scavenger hunt. “You have two minutes to find something that is red and blue and bring it back,” they instructed. I willingly stepped off my seat to go searching around my house, changing my zoom-focused perspective. Returning to the screen, I saw camera boxes filled with different objects. This type of activity, to highlight our humanity, to make the ordinary interesting, exemplified parts of the conference that resonated with my curiosity and my role as a communications manager.

This feeling around humanity deepened while I listened to keynote speaker Dr. Johnnetta Cole remind us that the humanities are social justice and that we need to make the field more accessible, supported by NEH Chairman Jon Parrish Peede’s comment not to dismiss those who do not get it. I am left with more motivation to work to broaden our audiences and support actions that work to bridge our differences.

Felicia Kelley, Project and Evaluation Director

Opening just a few days after the polls closed on November 3, the conference provided a welcome respite from the tumultuous election season. I always find this annual opportunity to connect with our academic and public humanities colleagues across the nation energizing. This year, it seemed especially valuable, given the enormity and urgency of our country’s challenges. It was encouraging to learn about all the good work being done in every state and territory, celebrate successes, explore solutions to common problems, and be inspired by leaders in our field. For me, the high point was the conversation between two distinguished scholar-practitioners, Smithsonian Institution Secretary Lonnie Bunch and Dr. Johnnetta Cole, who delivered the annual Capps Lecture. Both shared observations about the humanities’ power to transform lives (including their own) and their conviction that the humanities are essential to democracy. As Sec. Bunch said, not only do the humanities “illuminate the dark corners of our history”, enabling us to confront ugly truths that call out for change, they provide the means to “embrace ambiguity” and “grapple with complexity.” Only by cultivating our capacity to listen, understand, and empathize with others, especially those unlike us, will we be able to find common ground that can enable us to work together to build a better future for our divided nation.

Sheri Kuehl, Director of Development

Kudos to everyone who worked behind the scenes to make this first-ever virtual National Humanities Conference such an engaging and well-executed event. The tone for the conference was beautifully set by the opening Capps Lecture which was, in fact, anything but a lecture. It was a captivating conversation between Dr. Johnnetta Cole and Secretary Lonnie Bunch, and within seconds of their opening exchange, it was evident we were in for a treat. It was also evident to me that I should grab a pen and paper. Looking back at my notes, I am reminded that “it does no harm to be grateful” (Dr. Cole quoting an African proverb), as well as of Sec. Bunch’s assertion that “the humanities can illuminate the dark corners” by allowing us to “grapple with nuance, subtleties, and shade of gray.” I’ve also underlined Dr. Cole’s declaration that the humanities help us to “get over ourselves.” This brilliant conversation filled with empathy, kindness, humor, truth, resolve, and hope was the perfect overture to a conference filled with more of the same.

Another highlight was “Now is the Time” Reading Fredrick Douglass Together in 2020. Adroitly facilitated by Mass Humanities’ Director of Grants Katherine Stevens, this session examined the tradition of bringing readings of Douglass’s speech on the meaning of the Fourth of July to community spaces. The custom of members of the public taking turns reading portions of the speech has recently been played out virtually. We had a taste of this during the session as panelists and session attendees took turns reading a ten-paragraph section of the address. This short community reading in the public square of Zoom was moving and thought-provoking on many levels, not the least of which was its proof that public humanities programs are adaptable to and thriving in the virtual space.

John Lightfoot, Senior Program Officer

At this year’s National Humanities Conference, I had the privilege of facilitating a panel discussion on the California Documentary Project with the filmmaking teams behind the California Humanities-supported, and nationally distributed documentary film projects CRIP CAMP, UNLADYLIKE2020, and THE ASIAN AMERICANS. The session’s goal was to spotlight our grantees’ excellent work in bringing important and often overlooked histories to light and to peek behind the scenes and look at the role the humanities can play in documentary films.

At their best, documentaries provide a window into worlds we may never otherwise experience, allow us to get to know people we may have never met, and help us empathize with the contemporary challenges around us. They can also help us better understand who we are and where we come from by creating a more inclusive historical narrative. In this case, the film projects explore watershed—though until now—largely overlooked histories of the disability rights movement, women trailblazers of the Progressive Era, and the contributions and challenges of Asian Americans, the fastest-growing ethnic group in America. Topics discussed by panelists included the importance of humanities scholarship in providing context, depth, and perspective to their films, and the importance of making a strong and direct connection between history and contemporary life.

We are deeply grateful to filmmakers Jim LeBrecht and Nicole Newnham of CRIP CAMP, Charlotte Mangin and Sandra Rattley of UNLADYLIKE2020, and Renee Tajima-Peña of THE ASIAN AMERICANS for sharing their insight with us and helping to shift the historical narrative.

Renée Perry, Operations Coordinator

Although this is my second conference, it struck me that the strength of each one is the coordination and collaboration between state humanities councils and local nonprofit organizations. The strongest presentations I saw were those where the councils worked closely with and funded projects rooted in and important to their communities. It was inspiring to see the deep commitments to equity and social justice with communities, nonprofits, and academics working together.

Oliver Rosales, California Humanities Board Member and Professor of History, Bakersfield College

Attending this year’s National Humanities Conference was a delightful retreat from the regularity of Zoom meetings I’ve found myself in during the pandemic. I found particular engagement and connection in two sessions dealing with rural humanities and the community college—issues I care deeply about as a California Humanities board member.

One session entitled Co-Creating at the Crossroads: Rural Humanities Principles and Practices featured a digital humanities mapping and story-telling project affiliated with The History Center in Tompkins County (Ithaca, New York). History Center Executive director Ben Sandberg gave an enlightening presentation on History Forge, a digital mapping project that combines census data, historical maps, and user-driven artifacts based in the greater Ithaca community. I found the presentation helpful given my own efforts to create digital mapping and story-sharing platforms in the San Joaquin Valley of rural California. History Forge is also developing a prototype mapping model that can be used free-of-charge by other organizations developing community archive projects.

A second panel entitled The Humanities in Prisons, Mosques, Restaurants, and Other Community Settings featured several humanities faculty from Modesto College. This panel focused on the ways Modesto College faculty have utilized place-based learning across various humanities courses to promote rich learning experiences for students. California’s Central Valley is a region of diverse cultures but is also marked by dramatic inequalities and social marginalization. Capitalizing on the region’s diversity and creating innovative programming has enabled Modesto College to center cultures that are regularly on the periphery of mainstream regional culture.

Both sessions allowed me to examine the pulse of rural humanities and community colleges’ importance in advancing the humanities to underserved audiences.

Lucena Lau Valle, Program Officer

This year the National Humanities Conference was presented virtually for the first time, an important but temporary change from the conference’s usual in-person format. Despite the virtual format, I was profoundly moved by the humility, grace, and intellectual generosity brought by the conference’s participants and presenters, who included colleagues from state humanities councils, academics, culture bearers, museum professionals, and representatives from diverse philanthropic and cultural organizations.

Logging into the conference from our home offices, kitchen tables, bedrooms, and various other impromptu workspaces, the presenters discussed their efforts as public humanities practitioners, administrators and scholars committed to bringing members of the public opportunities to explore the humanities in their everyday lives. For over a week, I was immersed in sessions that explored a range of topics that included how to introduce and operationalize racial equity work in state humanities’ councils, a discussion of the role of the public humanities in non-academic community spaces, and a presentation exploring how to develop culturally responsive programming and grants. Above all, I was deeply moved by the many ways my colleagues in the field have adapted their work to support community members that have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the discussion that left me inspired, energized, and grounded, was the Capps Lecture, which featured a conversation between Dr. Johnetta Cole, an anthropologist, educator, museum director, and former college president with Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III, an educator, historian, museum curator, and administrator. Together Dr. Cole and Secretary Bunch spoke about the urgency and need for the intersection of the public humanities and social justice in our present moment of dynamic change as we reflect on the past, present, and future of our nation.

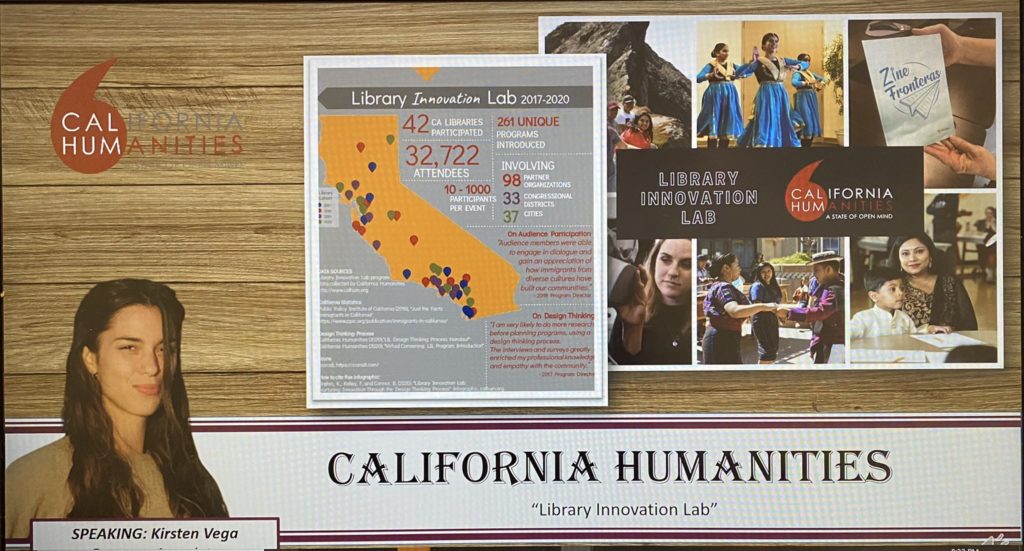

Kirsten Vega, Program Associate

What do colleges, universities, state humanities councils, museums, and libraries share in common? One thing that outsiders might not realize is that all have a seat at the National Humanities Conference, an annual event that explores the “impact and relevance of the humanities in everyday American life.” Since joining California Humanities in 2018, it has been a joy to spend time with inspiring colleagues from across states and sectors. This year, I attended not in Indianapolis as planned, but from a stool in my kitchen, squeezed between a KitchenAid Stand Mixer and a sink of dishes. The result was more inspiring and intimate than expected.

United by the strain of a difficult year, the camaraderie among colleagues was palpable, and spirits rose – corny, but true! – as we swapped stories of the humanities in quarantined life. In New York, a poster artist created Love Letters To Chinatown to collect handwritten odes to the neighborhood and post them in public – on storefronts, telephone poles, coffee stands – where they will be stumbled upon by strangers. I admire how this act creates intimacy and solidarity, allowing residents to once more interact with acquaintances in the neighborhood and air their emotions about its struggle. On a larger scale, Oregon Humanities connected strangers with their brilliant statewide pen pal program, Dear Stranger.

On the home front, it was a true honor to receive a Schwartz Prize for California Humanities’ Library Innovation Lab, a program which we are proud to say has reached over 33,000 Californians and 42 partner libraries since its inception in 2016. We hope this recognition will aid libraries across the country in their work to create more multi-cultural humanities programs for immigrants and new Americans.

Debra White, Grants Manager

This was the third National Humanities Conference that I have attended. I think it was the best one thus far. I found the virtual space more relaxing and focused than the usual in-person environment. It was easy to see and hear the speakers. I did not have to search for a seat. I found it easier to participate in the sessions’ breakout rooms without the usual distractions that new places and lots of people bring. I saw how the humanities connected to current crises, and most of the sessions ended on an optimistic note even though the conversations and topics were hard. Even listening to presenters walk through and explain the federal and NEH requirements on state councils through walking through a policy document one question at a time was interesting in this setting.

The most profound sessions for me explained, demonstrated, promoted the benefits of community dialogues using the Civic Dialog Method. The Civic Dialog Method is being used to bring strangers together to discuss race and COVID-19. The sessions started with defining different group interactions:

Conversation: Primary purpose is self-expression.

Discussion: Information and ideas are exchanged to accomplish a task or solve a problem.

Debate: Primary purpose is to “win” an argument by affirming one’s own views and discrediting other views.

Dialogues: Focused attention on listening and understanding.

In the breakout rooms, participants looked at photos, art, and literature and had their own community discussions with guided questions to provoke emotions and reflections. We were encouraged to allow the conversation to flow organically as words were shared. Everyone was expected to participate. Everyone was expected to accept the free-flowing wave of ideas without judgment or restraint. Everyone was expected to let go of the idea that something, other than people coming together to talk, had to result from the dialogues.

Julie Fry, President & CEO

During the summer of 2020, the Federation of State Humanities Councils – upon whose board I sit – had to make a decision about the National Humanities Conference in November: whether to conduct the conference as planned in Indianapolis, since planning was underway, or move to an all-virtual conference. Public safety during the pandemic made the decision a simple one. With our partners at the National Humanities Alliance, we recognized that bringing people together around the humanities, even virtually, was going to be critical in the run-up to the end of an extraordinarily challenging year.

The conference turned out to be a delight, all credit to the staff and leadership of each of the partner organizations, and to everyone who participated, including the keynote speakers, panel participants, and the over 900 registrants. Personally, I discovered this fun fact: it turns out that you can make a pie crust or pet your cat while listening to enlightening and energizing conversations rooted in the humanities! While I missed seeing people in person, it was also an excellent opportunity to expand the reach of the conference further and to more people. Kudos to everyone involved.

I was grateful to have the opportunity to participate on two panels. The first, Pursuing State and Local Policies to Fund the Humanities, provided insights from different parts of the country on the policy and advocacy efforts that it can take to garner non-federal government funding. The second, City/Cité: The Humanities at a Global Crossroad, shared the international exchange work we are part of between Oakland, California and Saint-Denis, France. This session possibly had the conference speaker from the furthest away, the island of Mayotte (a department and region of France) in the Indian Ocean.

I was particularly moved by the final keynote conversation between Maryland Humanities’ Andrea Lewis and award-winning author Jason Reynolds, which covered how he has been handling the pandemic, what he hears from his young readers about his impact on their lives, and his approach to writing Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You, an adaption of Ibram X. Kendi’s National-Book-Award-winning history Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. But we also learned how he became a writer; he didn’t grow up reading – no one in his life did – and he found his voice through writing rap lyrics. When he was asked how he decides how to tell a story, he replied “Writing is an art, not science, not just about structure and form. But you’ve got know the rules to break the rules.”