As part of a national celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Pulitzer Prize, California Humanities is convening a series of discussion forums throughout the state through the Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative. The fifth in the series features a conversation on “The Farmworker Movement in California” at the Fresno Art Museum. Pulitzer Prize-winner Miriam Pawel reflects on the lessons of the Movement as a guide to organizers and activists today. For more info on this forum and the series, please click HERE.

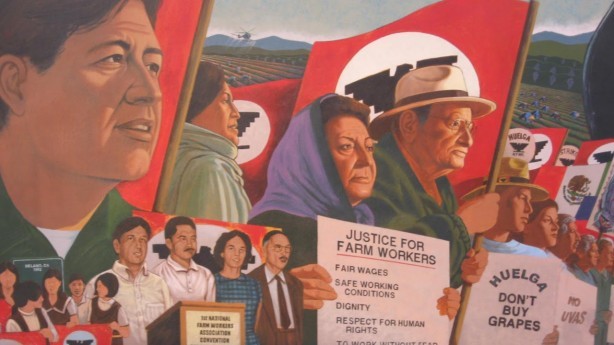

The Farmworker Movement in California: From Chavez Onwards

Fresno Art Museum

September 28, 2016 – 7:00pm

Miriam Pawel, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist

Dawn Mabalon, Associate Professor of History at San Francisco State University

Luis Valdez playwright & founder of El Teatro Campesino, moderator

Samuel Orozco, author and National News and Information Director of Radio Bilingüe

By Miriam Pawel

Fifty years ago, farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley made history: They won the first union contracts in the fields. Cesar Chavez burst into national prominence, leading a 300-mile march that began with a few dozen workers in Delano and ended with a rally of thousands at the state Capitol on Easter Sunday. Labor, religious, and civil rights leaders flocked to the California fields — to help, to learn, and to bear witness.

“The nation’s farm workers, historically low paid, poorly housed and often regarded as the forgotten men and women of the economy, may be near the dawn of a new era of union organization,” the New York Times declared on Sept. 3, 1966, after the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee won a crucial election against the largest grower in California. AFL-CIO chief George Meany predicted farmworkers would soon work in a unionized industry.

Many victories ensued over the next decade, and the United Farm Workers became a powerful force both in the California fields and the halls of Sacramento. The movement transformed the lives of thousands, and, for a time, Meany’s words appeared prophetic.

But today, farmworkers are once again non-unionized, poorly paid, and poorly housed. Once again, they are hired primarily by labor contractors, middle-men whose role Chavez worked to eliminate. And instead of farm labor becoming more like other industrialized work, the reverse has happened: Increasingly, workers in other sectors of the economy toil under the kind of conditions that Chavez fought.

Uber drivers complain they are paid less than minimum wage. Guestworkers are cheated out of wages and exploited by unscrupulous contractors. The “gig economy” has spawned murky legal ground and allowed employers to evade responsibility by categorizing workers as “independent contractors.”

Against this backdrop, the successes and failures of the farm worker movement decades ago take on new relevance, and new urgency. Farmworkers had virtually no legal protection (exempt from health, safety and labor laws); their union was bitterly opposed by presidents, governors, sheriffs, and most institutions of power. The story of how the poorest workers in California achieved their remarkable victories can and should help guide organizers and activists today.

As a journalist for more than 25 years, I focused on making sense of fast-breaking stories as they happened, holding officials accountable for actions, and shaping coverage that might influence policy in the future. Journalism, as the saying goes, is the first cut of history. As a historian for the last decade, I’ve been able to delve deeply into the past – with the same basic goals: To make sense of events in order that we might learn from them, and to provoke discussion about where to go from here. With rampant and intractable income inequality, I can think of no better time to study and debate the history and legacy of Cesar Chavez and the farmworker movement.

This forum is free and open to the public. For registration information, please click HERE.