Julie Fry, President and CEO

A national conference of more than 500 attendees takes a village to develop and deliver. I had the honor of being chair of the planning committee of the 2019 National Humanities Conference, #NHCOceania, a partnership of the Federation of State Humanities Councils (FSHC) and the National Humanities Alliance (NHA). You can read my blog, published on the first day of the conference. The conference for me was a whirlwind of meetings, discussions, more meetings, and pre-dawn walks on the beach. A highlight was, in my role as the Secretary of the FSHC board, reading the roll call of states and territories at the Annual Business Meeting. I was unabashedly moved by this duty; in my adult life, I never have the opportunity to read through the list publicly, with each state providing a geographically relevant delivery of “here”. For example, the Idaho Humanities Council responded with, “the spuds are here,” while Humanities Guåhan’s reply was, “Håfa Adai,” a traditional Chamoru greeting.

California Humanities staff and board in attendance made an investment in content by facilitating discussions or speaking on panels on a wide range of topics, from a working group focused on immigration, to a discussion of the Mellon-funded Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative, to discussions on building government relationships and fundraising. Back at work in Oakland after the conference, I found my mind drifting westward across the water. A flash of color reminded me of the fish in the hotel ponds, a breeze took me back to sitting on the grounds of the Bishop Museum listening to local navigators tell their stories, the smell of something sweet made me hungry for a malasada. All of that is to say that the conference affected all of my senses, as well as my mind, and I’ll never forget it.

Felicia Kelley, Project and Evaluation Director

The theme of this year’s National Humanities Conference (NHC), Roots and Routes: Navigation, Migration, and Exchange, and its setting in Hawai’i—for the first time ever off the mainland—was especially rich and meaningful for me. As always, the NHC is a communal crossroads, providing a place to meet new colleagues and deepen longstanding relationships. The conference organizers and hosts (the four Oceanic humanities councils) curated an exciting program that provided many engaging and thought-provoking experiences.

I found the closing event, a panel discussion about the contemporary revival of the ancient Polynesian art of long-distance seafaring, especially powerful. The three culture-bearers gave eloquent testimony about the ancient stories that inspired them and their communities, and the importance of maintaining resiliency in the face of enormous social, economic, and environmental challenges. By sharing their experience with us, these navigators provided a vision of how we might all act, guided by enduring human values and insights, to get to a safe haven that will ensure the survival of our species and our planet.

Lucena Lau Valle, Associate Program Officer

One of the most memorable parts of my time at NHC in Honolulu was the Program Officer’s Pre-Conference Day, which included a visit to the Mānoa Heritage Center. The Mānoa Heritage Center is a 3.5-acre property that was created to offer visitors learning experiences rooted in traditional Hawaiian cultural heritage and native ways of understanding the natural world. Upon arriving to the Heritage Center, I could hear birds calling in the distance and felt the gentle showers and breezes that intensified the earthy aromas of the native plants growing on the Heritage Center’s grounds. Our group was greeted by Heritage Center staff who began our time at the Center with an oli, a traditional Hawaiian chant with deep significance to history, place, and cultural memory. During our time at the Heritage Center, our group was also able to view the reconstructed Kūka‘ō‘ō Heiau, which is one of the only intact ancient Hawaiian temple sites in Honolulu. As visitors to this sacred space we were invited to share about our hometowns and voice our intentions for our visit. I felt gratitude to take part in this practice which gave so much reverence for our surroundings.

I was equally moved by the generosity of the Heritage Center’s staff and the Center’s founder Mary Cooke, who invited our group to tour her home—a space that is not formally open to visitors at this time. It was deeply inspiring to learn about the work undertaken by the Heritage Center’s staff who, with the support of a NEH Creating Humanities Communities grant, have spent the past few years creating place-based programs inspired by the heiau, the surrounding gardens of native Hawaiian plants, and have examined historic primary sources such as nineteenth century Hawaiian language newspapers to develop curriculum for K-12 students in Hawai’i.

Kirsten Vega, Program Assistant

“The past is a position,” anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot famously wrote in his 1995 book Silencing the Past. Trouillot’s insight bubbled into mind during my four days at the National Humanities Conference in Honolulu. It seemed to capture the sensibility of the public humanities practitioners and administrators I met who use their work to create an inclusive space for a plurality of voices and “positions” on the past. Public humanists invoke the past to discuss the present. For example, at Indiana Humanities, Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein prompted a statewide reading and discussion about the role of technology and science play in the 21st century.

When Mehanaokalā Hind of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs opened the conference, she introduced herself with the words, “I am an ancestor,” an insightful nod to the role we all play in producing history for future generations. With posterity in mind, National Endowment for the Humanities Chairman Jon Peede announced a new initiative, A More Perfect Union, which will support new strategies for teaching American civics education in a way that will “share the story of all the people.” The outlook for public engagement in civics looked good at the West Virginia Humanities Council, where their digital history guide on Clio is the third most popular website in West Virginia. The popularity of the 370 walking tours available on the site tells me that for West Virginians, the past is not a fixed “position” but a series of paths which weave into the present.

John Nguyen-Yap, Outreach & Advocacy Manager

Humility. That has been my go-to answer in recent months to the existential question of, “What do the humanities mean to you?” Humility is a perfect word to describe my experience at the 2019 National Humanities Conference both as a first-time attendee and also as a returning visitor to Hawai’i. I listened to welcoming presentations by the leaders of the Councils from Hawai’i, Guåhan, Northern Marianas Islands, and Amerika Samoa, and heard about their continued journeys in reclaiming, redefining, and restoring of the indigenous cultures throughout Polynesia in the context of various forms of colonization. I reflected on who and what I represented as a repeat visitor to Hawai’i especially in Waikīkī. It provided me an opportunity to reflect on what I can and should be doing as a staff member of California Humanities and member of the “humanist” community.

I thought about the importance of stories and, even more so, the craft and culture of storytelling. I thought about how histories, culture, traditions, self-actualization, resiliency, and persistence are carried primarily through storytelling—how storytelling and its many purposes thrive and are ever-present like water even when they are hidden until decoded by the lessons in those stories. I thought about the importance of authentic and complete histories being told from the voices and perspectives of those who were silenced and whose histories were attempted to be erased. I thought about those many layers throughout the days of the conferences.

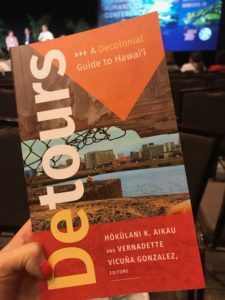

All of the sessions I attended related to those experiences even if some had no ties to Native Hawaiians or Polynesia. I attended numerous sessions about racial equity that talked about strategies of education and assessing impact and they all reflected on the importance of some act of humility whether from educators, exhibitors, or grant makers. Other sessions I attended provided concrete examples of telling the inclusive history of Hawai’i like the new book Detours that challenges the iconography of Hawai’i that is limited to a tourist dreamscape of palm trees and luaus, or the theater of Hawaiian Mission Houses that tells the authentic stories of Hawai’i and Native Hawaiians that were captured in the written journals of their missionaries. Thank you to the people and ancestors of Hawai’i and all the islands across Oceania for hosting us. Thank you for instilling in us your intrinsic human dignity and spiritual connection to the land, sea, and universe.

Claudia Leung, Communications Manager

As valuable as it is to hear from colleagues and scholars presenting in traditional formats in a conference space, the most exciting aspect of the National Humanities Conference to me is getting outside of the four walls of the hotel to visit community events and organizations—where the human aspect of our humanities work is really tangible. In an off-site session, I got to visit Hoʻoulu ʻĀina, a community-based land project on a 99-acre nature preserve in one of the lowest-income communities in Hawai’i, Kalihi. We started with an incredible farm-to-table meal, with all the ingredients sourced locally from the island, a feat since Hawai’i imports about 80% of its food.

After lunch, we took a tour of the farm, where we saw traditional seafaring canoes being built by Kalihi youth—including one made out of an invasive tree species. We were shown a traditional hale, or house, built by locals and used for community healing practices, along with an ʻahu, or altar, with medicinal plants growing nearby. The newest building on the property included a processing space for the natural medicines produced at the farm, some of which are prescribed by doctors at the local federally-qualified health center, Kōkua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Family Services, which is also Hoʻoulu ʻĀina’s parent organization. The space also included a room for the study and practice of traditional healing, including lomilomi massage, and a meeting area where earlier that day a local diabetes support group had met. Finally, on our tour, we visited the community garden, where rows of fresh kale were sprouting up and ripening turmeric plants towered above us.

The visit helped me to draw so many more connections between issues that are commonly not thought of as “humanities” concerns: holistic, indigenous health practices, food security, agroecology, and youth development, as well as more standard topics like storytelling, cultural practice, and preservation. Many thanks to Humanities Guåhan, the council that serves the people of Guam, who arranged this tour.

Debra White, Grants Manager

The moment that exemplified the Roots and Routes theme of the National Humanities Conference for me was seeing the sacred feathered cloak and feathered helmet of chief Kalaniʻōpuʻu safely resting in the Bishop Museum. However, without the aid of the guided tour by one of the Board Members from the Hawai’i Council for the Humanities, I would not have fully understood and appreciated the history of these garments that were on display. In 1779, when English explorer Captain James Cook docked his ship in Kealakekua Bay, the Hawaiian chief Kalaniʻōpuʻu greeted Cook with a demonstration of his goodwill by removing his cloak and helmet and placing them on the shoulders and head of the Englishman. After Cook died, the sacred clothing was taken back to England when the ship departed Hawai’i. The garments moved through the hands of several collectors and museums before ending up at the Dominion Museum in New Zealand. In 2016, the Bishop Museum received the cloak and helmet as a 10-year loan/gift from the New Zealand museum. The Board Member boasted with pride about this being the only cloak for which they knew exactly how it left and how it returned. To me this captured the “roots and routes” of the sacred garments.

John Lightfoot, Senior Program Officer

Most appreciated about this year’s National Humanities Conference in Honolulu was the thoughtful and thought-provoking emphasis on place. Whether celebratory or provocative, the focus on the unique historical, cultural, and political dynamics of Hawai’i and the Pacific Islands put the region’s complicated history and relationship with the United States in new perspective.

Mary Valentine, Board Chair

Attending the 2019 conference, I was again impressed with the breadth and depth and relevance of the presentations and discussions of issues that matter to us. Those issues were as varied as understanding the role of the humanities in discussions of immigration, the role of the humanities in creating community, growing public engagement in the humanities, and diversifying our revenue opportunities. The program appealed to the heart as well as to our minds as evidenced by the closing ceremony featuring three navigators who talked about traditional seafaring in the Pacific.

Praise should go to the California Humanities staff who played a visible and important role in the conference. At the end of the conference, I came away prouder than ever to be a part of the humanities community and particularly proud of California Humanities.