“Watsonville Is in the Heart: A Public History Initiative” is a community-led project that seeks to uplift the Filipino labor and migration narratives found in the city of Watsonville. The project recently received a Humanities for All Quick Grant to help fund the community work and develop a digital archive and exhibition at the Watsonville Public Library. For this blog post, Program Officer Lucena Lau Valle interviewed Project Director Kathleen Gutierrez and her team to discover how this project will gather and preserve historical documentation on Filipino labor and migration in partnership with community members. The end of this blog features a clip of an oral history interview with Antoinette Yvonne DeOcampo-Lechtenberg, daughter of first-generation Filipino migrant manong, Paul DeOcampo, by research assistant Olivia Sawi.

What inspired the title of your project, “Watsonville Is in the Heart”?

The title comes from the novel America is in the Heart, published in 1973 by Filipino writer and activist Carlos Bulosan. Regarded today as part of the Asian American literary canon, the novel brings light to the history of migrant Filipino labor to the United States in the first part of the twentieth century. Because of Watsonville’s indelible importance to this history, our community partner—and really, the driving force of this California Humanities-funded initiative—Dioscoro “Roy” Recio, Jr., decided upon our project name. We certainly aren’t the first to pay homage to the novel or writer in this way. The late and beloved scholar Dawn Mabalon titled her book on the Filipino community of Stockton Little Manila is in the Heart (2013), and the University of California, Davis has a research center inspired by Bulosan’s life’s work.

Your project captures the hidden histories of the manong generation, who were the first generation of Filipino migrants arriving to the U.S. in the first decades of the twentieth century. Can you tell us more about how the manong generation shaped the farmworker movement in California?

I think one cannot fully comprehend twentieth-century agricultural and farm labor history in California without the manong generation. Thousands of young men from the Philippines arrived in the fields of California in the early twentieth century. Beginning in 1898, U.S. colonization of the Philippines spurred this migration, and the first waves of migrant labor settled in Hawai’i and along the western seaboard of the United States. Young Filipino men mainly from the Ilocos and Visayas regions of the archipelago worked alongside other migrant farming communities, many following the growing and picking seasons.

The manongs faced—and challenged—the brutality of xenophobic policies that had similarly befallen Chinese and Japanese migrants. In Watsonville, this not only took the form of anti-miscegenation laws and stipulations that prevented Filipino land ownership. It also manifested in anti-Filipino riots, orchestrated by racist and begrudged white residents, that apexed in the 1930 murder of Fermin Tobera, a young migrant worker. Yet, in the face of systemic prejudice and inhumane labor conditions, the manongs built ties that extended beyond customary kin relations. They made homes, established communal lodges, and created sanctuaries to harbor survival in the everyday. In the mid-twentieth century, they organized alongside Mexican migrant labor and were the key organizers behind the Delano grape strike, among other actions. Figures like Bulosan, Philip Vera Cruz, and Larry Itliong remain significant to this history. More detailed accounts of this generation and excellent studies are out there. I highly recommend the Bulosan novel, Mabalon’s body of work, The Third Asiatic Invasion, by Rick Baldoz, and Marissa Aroy’s documentary, Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers.

How will your program allow audiences to explore the stories of labor and migration? How will your program give audiences an opportunity to explore the stories of labor and migration?

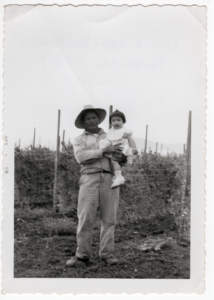

The Watsonville is in the Heart team is excited to work alongside the children of the manong generation. While the vast majority of the first manongs have long since passed, their children continue to preserve their stories. Since Spring 2021, our team has been conducting oral history interviews and scanning and preserving precious images, documents, and other personal ephemera that capture the dynamism of Watsonville manongs and their families. Our California Humanities-backed program will bring these stories to the public in the form of four “Talk Stories,” public fora—virtual and in-person—to discover an angle of the history we’ve so far captured. We are partnering with documentarians Marissa Aroy and Geoffrey Dunn and community members Eva Alminiana Monroe and Juanita Sulay Wilson, among others, to showcase narratives of Filipino labor, of the complexities of multiracial families—of which many manong were apart because of the comparatively smaller Filipina population that migrated in the early twentieth century—and of the women of Watsonville who are committed to preserving the past.

Our Talk Story series will culminate in the launch of our digital archive, currently spearheaded by Meleia Simon-Reynolds, a Ph.D. student in History at UC Santa Cruz. The digital archive will feature oral history recordings, video clips, and digitized material to showcase the history most important to our community partners. Hosted by UC Santa Cruz, the digital archive will be available to the public. In addition, it will feature curated virtual exhibits by our project team members, like Christina Ayson Plank, a History of Art and Visual Culture Ph.D. candidate at UCSC.

Collecting historical documentation with community members and creating a web archive is integral to your project. Why do you feel this undertaking is essential?

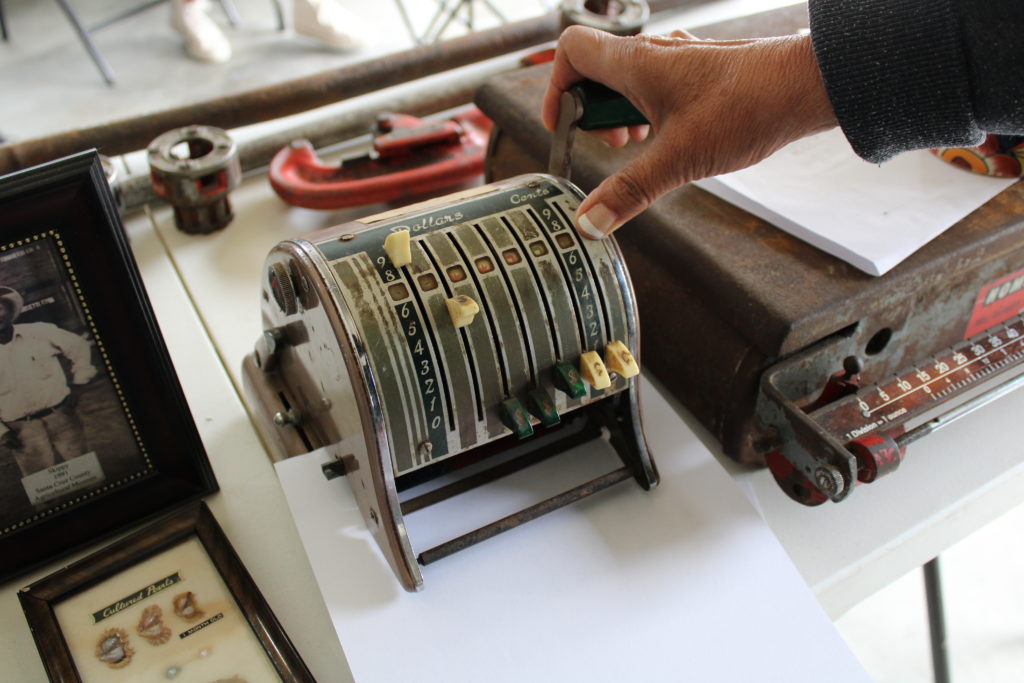

At the very outset of this project, Roy made clear: the story of Watsonville needs not only to be preserved but to be shared. Through our web archive, we’re not only aiming to preserve essential media. We are uplifting the excellent archiving strategies that some of the community members are already deploying. This looks like bringing attention to their “archive drives.” At these events, a community member sends a call-out for others to bring their photos and documents to a central location and to share their stories about their material as they scan onto hard drives for preservation. For the last two years, Roy has printed calendars that feature family histories from Watsonville. We’ve also had the pleasure of working with personal collections that have been maintained with precision and care. To our team, all this work falls under the umbrella of public history. While this is a new intellectual domain for me—one that I continue to learn about through my generous colleagues and bright collaborators—I know that it’s integral to making history, in general, more accessible (and fun and community-inspired) terrain.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Yes! For more information on this work, please check out The Tobera Project, the community-run partner organization that functions as the core of Watsonville is in the Heart. Folks can also visit our project page through The Humanities Institute of UC Santa Cruz.

Enjoy this audio clip of research assistant Olivia Sawi interviewing Antoinette Yvonne DeOcampo-Lechtenberg, daughter of manong Paul DeOcampo.

Media credits: We thank the DeOcampo family and Johnny Rosser for the media shared in this post.